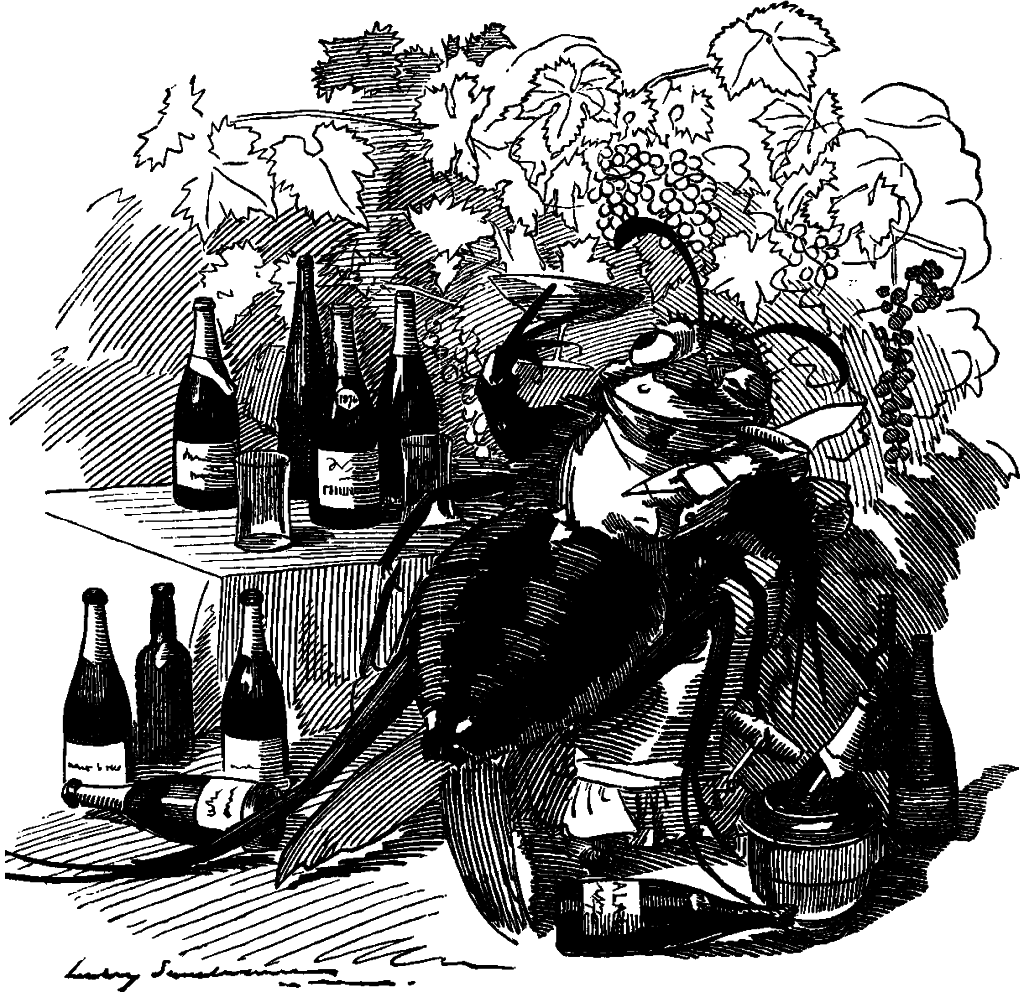

The phylloxera, a true gourmet, finds out the best vineyards and attaches itself to the best wines

Cartoon from Punch, 6 Sep. 1890)

On December 13, 1838, French botanist Pierre-Marie-Alexis Millardet was born. He is best remembered for his work dealing with plant pests, especially in the vineyards of France that were infested by the destructive Phylloxera in the 1860s.

Pierre Millardet – Background

Millardet attended the Collège de l’Arc and later Besançon, he studied medicine as well as nature science at the University of Freiburg and Heidelberg, where he did studies on monocotyledons and lichens. After his return to France, he obtained a doctorate in natural sciences and a doctorate in medicine, before becoming professor of botany at the University of Strasbourg around 1868. It is assumed that Millardet stayed there for about six years and then changed his position to the University of Nancy. [1]

The Phylloxera Catastrophe

In 1874, Millardet was commissioned by the Académie des Sciences to study phylloxera. The aphid relative, which originated in North America, was introduced in the 1860s by vines from the east coast of America via London into southern France (proven from 1863 onwards) and spread rapidly from there to all European wine-growing regions during the phylloxera invasion. As a consequence, European viticulture suffered dramatic devastation, the so-called “phylloxera crisis” or “phylloxera catastrophe”. France was particularly hard hit. Between 1865 and 1885, phylloxera destroyed large parts of the French wine-growing regions, which had only been replaced by new vines from America around 1850 after the mildew crisis. This had catastrophic consequences for French agriculture. In total, almost 2.5 million hectares of vineyards were destroyed in France alone. In France, one of the desperate measures of grape growers was to bury a live toad under each vine to draw out the “poison”. Areas with soils composed principally of sand or schist were spared, and the spread was slowed in dry climates, but gradually the aphid spread across the continent.

The Battle against Phylloxera

In 1870, the French government set up a commission to combat phylloxera under the chairmanship of the chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas, followed in 1885 by Louis Pasteur [5] as chairman, who had already been a member of the commission. However, the efforts of the commission were unsuccessful in the long run, as it preferred chemical pest control. It is believed that in 1874, Millardet was asked by the government to research the causes of phylloxera and find solutions. [2,3]

Pierre Millardet and a fellow botanist named Jules Émile Planchon intended to control the infestation by using American grape vines that were believed to be resistant to phylloxera. Building on the works of Victor Ganzin and Georges Couderc, Millardet performed numerous experiments and began focusing on hybrid crosses between vinifera and the Native American varieties. His initial goal was to create hybrids that contained resistances found in native American varieties without altering the wine’s quality. Unfortunately, Millardet failed doing so, but his research was quite essential for the solution of grafting Vitis vinifera onto American rootstock. This method was probably advanced by Charles Valentine Riley and Planchon and is the preferred method until this day. It allows the customization of the rootstock to soil and weather conditions and does not interfere with the development of the wine grapes. [2]

Later Life

In 1876, Millardet was appointed to the chair of botany at the University of Bordeaux. There he worked on the breeding of hybrid vines and also created some new rootstock vines. By chance, he also discovered bordelaise pulp, a mixture of copper sulphate and lime as a remedy for downy mildew, a fungal disease that had been introduced from America and had caused devastating losses in some European wine-growing regions. Millardet had noticed that the vines of one vineyard were infected with this disease, but the neighboring vineyard was not – although the grapes of these healthy vines were covered by a light blue layer. He interviewed the winegrower, who said that he sprayed the grapes with a mixture of milk of lime and copper sulfate. Millardet developed this recipe further with his chemistry colleague Ulysse Gayon.

Gino Carnevale, VEN290 Spring 2020: Update on phylloxera research, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Short Biography if Pierre Millardet at Britannica

- [2] There’s Still No Cure For Grape Phylloxera

- [3] Dying on the Vine

- [4] Louis Pasteur – the Father of Medical Microbiology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Histoire des principales variétés et espèces de vignes d’origine américaine qui résistent au phylloxera. Paris, Masson; Bordeaux, Féret; Milan, Hoepli, 1885.

- [6] Pierre-Marie-Alexis Millardet at Wikidata

- [7] Gino Carnevale, VEN290 Spring 2020: Update on phylloxera research, UC Davis Viticulture & Enology @ youtube

- [8] Timeline of French Mycologists via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #26 | Whewell's Ghost