Oliver Evans (1755 – 1819)

On September 13, 1755, American inventor, engineer and businessman Oliver Evans was born. A pioneer in the fields of automation, materials handling and steam power, Evans was one of the most prolific and influential inventors in the early years of the United States. He is known for designing and building the first fully automated industrial process; America’s first high-pressure steam engine; and the first (albeit crude) amphibious vehicle and American automobile.

Early Years of an Inventor

Oliver Evans was born in Newport, Delaware, USA, the son of a farmer. He received only little education as a child and was apprenticed to a wheelwright and wagon-maker in Newport and later became a specialist in forming the fine wire used in textile cards, which were used to comb fibers in preparation for the spinning process to make thread or yarn. He felt the desire to make the process more efficient and developed a machine that speeded the card manufacturing process, producing around 1,500 teeth every minute. He began to work on the Newcomen steam engine from the end of 1772, which he wanted to improve to the point where it could be installed in a vehicle.[4] From 1778 he served as a soldier in the American War of Independence (1775-1783).

Easing the Miller’s Labour

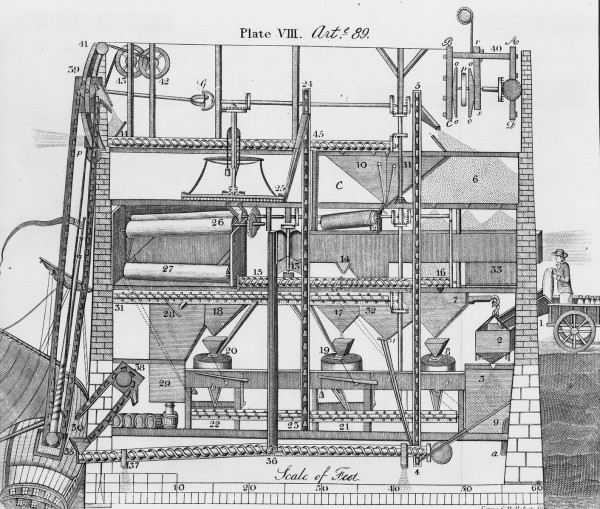

During the 1780s, Oliver Evans became more enthusiastic about flour mills. Back then, the operation of mills was very labor-intensive and step by step the grinding, cooling, sifting, and packing part were mechanized. Still, Evans viewed the process as highly inefficient, and the quality of milled as poor. In 1783, two of Evans’s brothers began building a mill in Newport on part of the family’s farm estate. Two years later, the mill opened and was mostly of a conventional design, but over the next five years Evans began to experiment with inventions to reduce the reliance upon labor for milling. Moving wheat from the bottom to the top of the mill to begin the process was the most onerous task of all in contemporary mills. Evans’s first innovation was a bucket elevator to facilitate this process.

Towards a fully automated Mill

Another labor-intensive task was that of spreading meal. This came out of the grinding process warm and moist, needing cooling and drying before it could be sifted and packed. Traditionally the task was done by manually shoveling meal across large floors. In response, Evans developed the “hopper boy”, a device which gathered meal from a bucket elevator and spread it evenly over the drying floor — a mechanical rake would revolve around the floorspace. While trying to get some financial support for constructing further fully automated mills, Evans kept developing the prototype at his brothers’ farm. After years of trying to monetize the project, Evans’s designs were finally given a trial on larger scales and adopted elsewhere.

Evan’s Milling Technology

In 1789 when the Ellicotts, a progressively minded Quaker family in Baltimore, invited Evans to refit their mills on the Patapsco River. The refits proved a success, and Evans worked with Jonathan Ellicott to develop a modified form of Archimedean screw that could act as a horizontal conveyor to work alongside the vertically orientated bucket elevators. Evans’s inventions were given a major boost when leading miller Joseph Tatnall converted his mills to the Evans system, and estimated that in one year the changes saved his operation a small fortune amounting to $37,000. Local millers quickly followed suit, and Brandywine Village was soon a showcase for Evans’s milling technology.

Steam Engines and Transportation

While in Europe, the development of steam engines was mostly driven by pioneers including Thomas Newcomen [4] and James Watt,[5] Oliver Evans started considering the potential applications of steam power for transportation. In 1801, he wanted to work on a steam carriage and focused on a reciprocating engine, not only for his steam carriage ideas, but also for industrial application. He further recognized that a high-pressure steam engine would be essential to the development of a steam carriage because they could be built far smaller while providing similar or greater power outputs to low-pressure equivalents. By then, Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot [6] had conducted some experiments with high-pressure steam engines and Evans did further developments, resulting in a high-pressure steam engine design that had a higher power-to-weight ratio that prevailing designs, making locomotives and steamboats practical. His first engine was powered by a double-acting cylinder six inches in diameter and with a piston stroke length of eighteen inches. The output of the machine was approximately five horsepower. However, Evans’ steam engine was just a fraction of the size of pre-existing machines. Evans unveiled his engine at his store and put it to work crushing plaster of Paris and, more sensationally, sawing slabs of marble. His marketing campaign paid off and Oliver Evans’ steam engine became a success.

The Oruktor Amphibolos

Evans received a patent for his new steam engine in 1804, and set about looking for commercial applications. After an early setback, the Philadelphia Board of Health was concerned with the problem of dredging and cleaning the city’s dockyards and removing sandbars: in 1805 Evans convinced them to contract him to develop a steam-powered dredge. The result was the Oruktor Amphibolos, or “Amphibious Digger”. The vessel consisted of a flat-bottomed scow with bucket chains to bring up mud and hooks to clear away sticks, stones and other obstacles. Power for the dredging equipment and propulsion was supplied by a high-pressure Evans engine. The Oruktor Amphibolos is believed to have been the first motorized amphibious craft. Although Evans himself claimed it proceeded successfully around Philadelphia, the great weight of the craft make land-propulsion based on its limited engine capacity and jury-rigged power train fairly improbable over any significant distance. It is similarly unknown how well, if at all, the Oruktor functioned as a steamboat, and Evans’s claims on this point vary significantly over the years.

Last Years

A serious setback was the non-renewal of his milling patents in 1808, which deprived him of his livelihood. He completed his second book, which was aimed at designers of steam engines. In 1808, the US Congress re-established his rights with validity until 1830. He spent his last years building up the Mars Iron Works and the Fairmount Engine Works. Gradually his steam engines were sold. In 1816 his wife died. In 1818 he married Hetty Ward from the Bowery in New York. There he fell ill with pneumonia in 1819. Oliver Evans died here on April 5, 1819, of a heart attack after the news reached him that the Mars Iron Works had burned down. The fire had been deliberately started by an apprentice of the company, apparently without any deeper reason. Evans’ all plans and drawings, and thus his life’s work, became a plunder of the flames.

Richard Bulliet, The Early Industrial Revolution, 1760-1851 [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Oliver Evans at Britannica

- [2] Oliver Evans at Today in Science

- [3] Oliver Evans at the University of Houston

- [4] Thomas Newcomen and the Steam Engine, SciHi Blog

- [5] James Watt and the Steam Age Revolution, SciHi Blog

- [6] Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot and the Automobile, SciHi Blog

- [7] Evans, Oliver (1795). The Young Mill-wright and Miller’s Guide. Philadelphia, PA: Oliver Evans.

- [8] Evans, Oliver (1805). The Abortion of the Young Steam Engineer’s Guide. Philadelphia, PA: Fry & Kammerer.

- [9] . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- [10] Oliver Evans, a biography from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- [11] Richard Bulliet, The Early Industrial Revolution, 1760-1851, History W3903 section 001, Columbia University @ youtube

- [12] Oliver Evans at Wikidata

- [13] Ferguson, Eugene S. (1980). Oliver Evans: Inventive Genius of the American Industrial Revolution. Wilmington, DE: Eleutherian Mills-Hagley Foundation

- [14] Bathe, Greville; Bathe, Dorothy (1935). Oliver Evans: A Chronicle of Early American Engineering. Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- [15] Timeline of Millwrights, via Wikidata and DBpedia