Enhanced version of Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras (1826 or 1827), the earliest surviving photograph of a real-world scene, made using a camera obscura

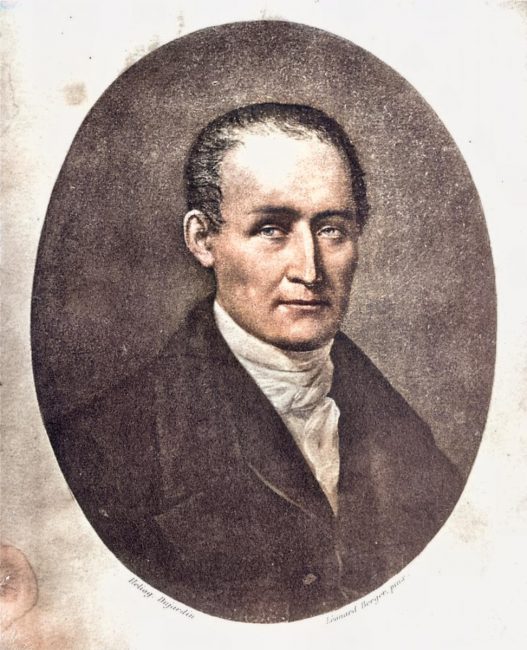

On March 7, 1765, French inventor Nicéphore Niépce was born, who is best known as one of the inventors of photography and a pioneer in the field. He developed heliography, a technique used to produce the world‘s first known photograph in 1825.

Early Life

Niépce was born in Chalon-sur-Saône, Saône-et-Loire, where his father Claude Niépce was a wealthy lawyer and the king’s counsellor, which caused the family to flee the French Revolution. His older brother Claude, who later was also his collaborator in research and invention, died half-mad and destitute in England, having squandered the family wealth in pursuit of non-opportunities for the Pyréolophore, the world’s first internal combustion engine. From 1780 to 1788, his studies at the Colleges of the Oratorians in Chalon-sur-Saône, Angers and Troyes gave Nièpce a glimpse of an ecclesiastical career, but it seems that the young man’s vocation was blunted. He renounced the priesthood and joined the revolutionary army in 1792.

Staff Officer under Napoleon and Lithography

A cut to Niépce’s scientific career depicted his duties as a staff officer under Napoleon, spending a number of years in Italy and on the island of Sardinia. Due to health issues he later on served as an administrator and eventually resigned in 1795 to continue his research along with his older brother Claude. However, until 1811 he remained an officer in the French army; between 1795 and 1801 he managed the district of Nice. Then together with his older brother Claude Niépce he devoted himself to mechanical and chemical works in his hometown and from 1815 to lithography.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1765-1833

First Photographic Experiments

First approaches in the field of photography were made by Niépce in the early 19th century. The date of Niépce’s first photographic experiments is uncertain. He was led to them by his interest in the new art of lithography, for which he realized he lacked the necessary skill and artistic ability, and by his acquaintance with the camera obscura, a drawing aid which was popular among affluent dilettantes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The camera obscura’s beautiful but fleeting little “light paintings” inspired a number of people, including Thomas Wedgwood [5] and Henry Fox Talbot[6], to seek some way of capturing them more easily and effectively than could be done by tracing over them with a pencil.

Bitumen in Lavender Oil

Letters to his sister-in-law around 1816 indicate that Niépce had managed to capture small camera images on paper coated with silver chloride, making him apparently the first to have any success at all in such an attempt, but the results were only negatives. Moreover, he could find no way to stop them from darkening all over when brought into the light for viewing. Niépce turned his attention to other substances that were affected by light, eventually concentrating on Bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt that had been used for various purposes since ancient times. What interested Niépce was the fact that the bitumen coating became less soluble after it had been left exposed to light. Niépce dissolved bitumen in lavender oil, a solvent often used in varnishes, and thinly coated it onto a lithographic stone or a sheet of metal or glass. After the coating had dried, a test subject, typically an engraving printed on paper, was laid over the surface in close contact and the two were put out in direct sunlight. After sufficient exposure, the solvent could be used to rinse away only the unhardened bitumen that had been shielded from light by lines or dark areas in the test subject. The parts of the surface thus laid bare could then be etched with acid, or the remaining bitumen could serve as the water-repellent material in lithographic printing.

The Heliography

Nièpce called the new method heliography, or sun writing. He did everything he could to create a permanent picture that would not fade in light and his first known success set in around 1822. He used it to create what is believed to have been the world’s first permanent photographic image, a contact-exposed copy of an engraving of Pope Pius VII, but it was later destroyed when Niépce attempted to make prints from it. The earliest surviving photographic artifacts by Niépce, made in 1825, are copies of a 17th-century engraving of a man with a horse and of what may be an etching or engraving of a woman with a spinning wheel. They are simply sheets of plain paper printed with ink in a printing press, like ordinary etchings, engravings, or lithographs, but the plates used to print them were created photographically by Niépce’s process.

The Oldest Photograph

Niépe’s first real success in using bitumen to create a permanent photograph of the image in a camera obscura came in 1824. That photograph, made on the surface of a lithographic stone, was later effaced. In 1826 or 1827 he again photographed the same scene, the view from a window in his house, on a sheet of bitumen-coated pewter. The result has survived and is now the oldest known camera photograph still in existence. The exposure time required to make it is usually said to have been eight or nine hours, but that is a mid-20th century assumption based largely on the fact that the sun lights the buildings on opposite sides, as if from an arc across the sky, indicating an essentially day-long exposure.

Collaboration with Daguerre

Nicéphore Niépce’s collaboration with Louis Daguerre began in 1829, and together they were able to create the physautotype process, an improved process that used lavender oil distillate as the photosensitive substance.[4] The partnership lasted until Niépce’s death in 1833, but Daguerre continued experimenting with several new photography techniques. Daguerre succeeded to implement an improved process he named “daguerréotype“, after himself. In 1839 he managed to get the government of France to purchase his invention on behalf of the people of France.

Later Years

During his life time and beyond, Niépce was able to build up a reputation as a pioneer in photography. He also was part of several furehr inventions, like pyréolophore, a combustion engine or the improvement to the marly machine in 1807. In 1818 Niépce became interested in the ancestor of the bicycle, a Laufmaschine invented by Karl von Drais in 1817.[9] He built himself a model and called it the vélocipède (fast foot) and caused quite a sensation on the local country roads. He furthermore improved his machine with an adjustable saddle and contemplated even about motorizing his machine. Niépce died in 1833 in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, about 7 km south of Chalon-sur-Saône, without having succeeded in commercially exploiting his invention.

Philippa Wright, Niépce in England, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Made How – biography of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

- [2] History of Photography – Nicéphore Niépce

- [3] Website about Niépce

- [4] Making Photography Really Operational – Louis Daguerre, SciHi Blog

- [5] Thomas Wedgwood – possibly the First Photographer, SciHi Blog

- [6] Photographic Pioneer Henry Fox Talbot, SciHi Blog

- [7] More pioneers of photography at SciHi Blog

- [8] Joseph Niépce at Wikidata

- [9] Karl Drais and the Mechanical Horse, SciHi Blog

- [10] Philippa Wright, Niépce in England, 2011, The Royal Society @ youtube

- [11] Timeline for Joseph Nicéphore Nièpce, via Wikidata