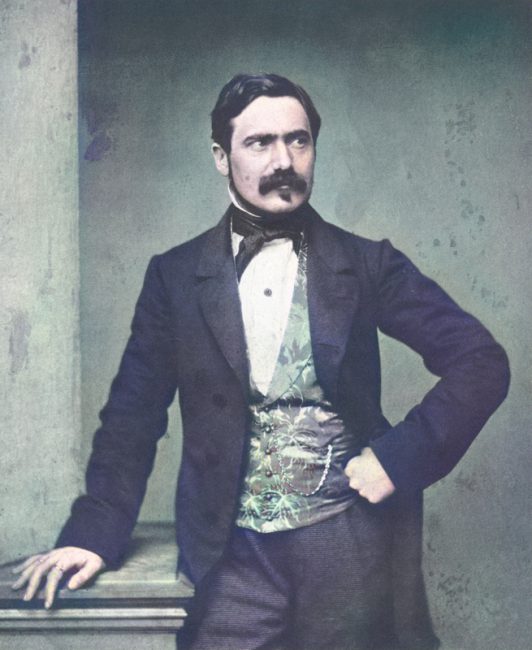

Max von Pettenkofer (1811-1901), photo by Franz Hanfstaengl, ca. 1860

On December 3, 1818, Bavarian chemist and hygienist Max Joseph von Pettenkofer was born. In his early career worked on industrial chemical processes and analysis of urine and bile acids, but today he is remembered in connection with his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal. He also developed standards for adequate ventilation in schools and hospitals.

“From time to time we send our underwear to be washed – instead of taking a bath ourselves.”

– Max von Pettenkofer [9]

Max von Pettenkofer – Youth and Education

Max von Pettenkofer was born on an isolated farm at Lichtenheim near Lichtenau on the northern edge of the old Bavarian Donaumoos as the fifth of eight children of the farmer Johann Baptist Pettenkofer (1786-1844) and his wife Barbara Pettenkofer (1786-1837). The family situation was very poor. To attend school he was given to Munich by his uncle Franz Xaver Pettenkofer, who was a royal Bavarian court and personal pharmacist. In 1837 Max Pettenkofer passed his school-leaving examination at the Munich Old High Schoo. He began studying natural science, pharmacy and, from 1841, medicine and chemistry at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. It was also his uncle who trained Max as a pharmacist from 1839. He then continued his studies in 1841 and graduated in 1843 with a doctorate in medicine, surgery and obstetrics. At the same time he obtained his license as a pharmacist. His first publication came out in 1842. In it he described a method for the detection of arsenic and for the separation of arsenic and antimony. He then studied chemistry at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg and then moved to the Hessische Ludwigs-Universität in the laboratory of Justus von Liebig at Gießen .[4]

Academic Career

Since Max Pettenkofer did not find employment after graduating from university in Giessen, he returned to Munich and devoted himself to poetry for the time being. The result was the “Chemische Sonette” (Chemical Sonnetts), which appeared in printed form in 1890. In 1845 he accepted a position at the Bavarian Main Mint. Here he dealt with processes for the refined extraction of gold, silver and platinum during the minting of the crown taler. In 1847 he was appointed professor for pathological-chemical investigations at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich . His lectures from this period were entitled “Dietary Physiological Chemistry” and “Public Health Care“. Important inventions from this period were his proposals for an improved method for the production of cement in 1849. A year earlier he had invented the copper amalgam dental filling. When his uncle died in 1850, he also took over the management of the court pharmacy. In 1862 he participated in a very successful company. It imported meat extract from Uruguay under the name “Liebigs Extract of Meat Companie” with headquarters in London. In the years 1864/65 he held the office of Rector of the University of Munich. In the same year he became the first German professor of hygiene in Munich and the first professor of this subject; from 1876 to 1879 the first hygiene institute was built.

X, Y, and Z

Max von Pettenkofer proposed that three factors he named X, Y, and Z were necessary in order for a cholera epidemic to break out. One of the three factor, X, was the specific pathogen which was typically found in the soil. Y represented the local and seasonal preconditions that allowed the pathogen to transform into a contagious miasma. Z then stood for the individual susceptibility to the disease. To compare this with Robert Koch,[3] when he discovered the cholera bacterium in 1884, Pettenkofer claimed that this germ was the X in his own theory. The composition of the soil and its interaction with groundwater was especially important to Pettenkofer’s theory, which is sometimes known as ‘contingent contagionism’ or ‘localism’.

Causing an Epidemic

It was Pettenkofer’s central belief that the cholera germ had to transform or “ferment” under these favorable circumstances before it could become contagious and cause an epidemic. Isolated from these circumstances, the cholera germ could not, in his view, cause disease. Pettenkofer famously demonstrated the strength of this belief in 1892 by drinking a quantity of water infected by pure cultures of the cholera bacillus. Though he did end up getting somewhat ill, he did not develop a full-blown case of cholera.

Robert Koch and the Cholera Germ

“Send me some of your so-called cholera bacilli, and I will prove to you how harmless they are!”

– Max von Pettenkofer, [12]

Pettenkofer’s results caused wide discussions in the scientific community. As he argued that cholera is mainly a waterborne illness and is not typically spread from person to person by direct contact many started to officially refute Koch’s bacterial theory of cholera transmission. During the 1860 and 1870s, Pettenkofer had probably his most influential period. He controlled the Cholera Commission for the German Empire until 1884, when Robert Koch’s discovery of the cholera germ fundamentally altered the terms of the discussion. Koch denied that the cholera germ underwent any transformation before becoming contagious, and he asserted that the cholera bacillus was spread most easily through water, not soil. Robert Koch was a supporter of quarantine and disinfection and his advice on how to prevent cholera was completely different from Pettenkofer’s. His recommendation for the strong state intervention that quarantine and disinfection campaigns required fit well with the German government’s priorities, and Pettenkofer’s localized and individualist approach fell out of favor.

Urban Hygieny

Max Pettenkofer presented his ideas on human health and urban hygiene to the Bavarian King Ludwig II at a private audience in 1865. Ludwig then brought about a ministerial resolution, with which the scientific subject “Hygiene” was appointed a nominal subject on 16 September 1865. In the following years he fought for the hygienic renovation of the city of Munich. By 1883 he had succeeded in establishing an exemplary drinking water supply and an efficient sewage system (alluvial sewerage), thus bringing considerably improved living conditions to the city. In 1882, Bavaria’s King elevated Max Pettenkofer to hereditary nobility.

Last Years

“Mere empiricism exhausts and repeats itself, science leads to steady progress, and the future belongs to it.”

– Max von Pettenkofer, [12]

Plagued by increasing pain and severe depression, Max von Pettenkofer shot himself at the age of 82 in his Hofapotheker apartment in the Munich Residency. The autopsy revealed chronic meningitis and cerebral sclerosis. Pettenkofer has published more than 20 monographs and 200 original articles in scientific and medical journals. His achievements as founder of hygiene, pioneer of environmental medicine, experimental field researcher, chemist and nutritional physiologist have been and continue to be recognized worldwide. Medical chemistry also owes him useful detection methods for arsenic (Marsh sample), sugar and urinary components. For his scientific achievements, he was admitted to the Prussian Order of Pour le Mérite for Science and the Arts on 24 January 1900.

Snowden, Frank (2010). “Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600: Lecture 13 — Contagionism versus Anticontagionism”

Referencs and Further Reading:

- [1] Max von Pettenkofer at Harvard

- [2] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Pettenkofer, Max Joseph von“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [3] Robert Koch and his Fight against Tuberculosis, SciHi Blog

- [4] Justus von Liebig and the Agricultural Revolution, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or about Max von Pettenkofer at Wikisource

- [6] Snowden, Frank (2010). “Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600: Lecture 13 — Contagionism versus Anticontagionism”. Open Yale Courses. Yale University.

- [7] Max von Pettenkofer at Wikidata

- [8] The Father of Hygiene, Science History, at LMU Munich, 12/3/2018

- [9] Eberhard J. Wormer: Pettenkofer, Max Josef. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, S. 271–273

- [10] Rainer Albert Müller: Pettenkoffer, Max von. In: Karl Bosl (Hrsg.): Bosls bayerische Biographie. Pustet, Regensburg 1983

- [11] Locher, Wolfgang Gerhard (November 2007). “Max von Kettenkoffer (1818–1901) as a Pioneer of Modern Hygiene and Preventive Medicine”. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 12 (6): 238–245.

- [12] Quotes by Max von Pettenkofer at Aphorismen.de

- [13] Timeline of Hygenists, via DBpedia and Wikidata