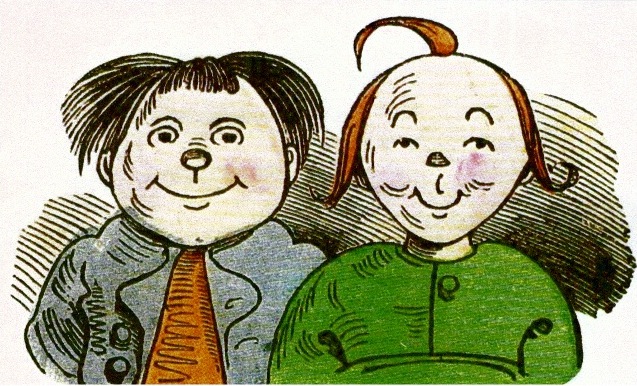

Max and Moritz by Wilhelm Busch (1865)

On April 4, 1865, Wilhelm Busch published his famous ‘Max and Moritz‘ (in the German original: Max und Moritz – Eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen), a famous German language illustrated story in verse, considered to be an early precursor of comic strips. Actually, if you are not by chance a German native speaker, you probably might never have heard of satirical author, illustrator and painter Wilhelm Busch, who was famous in the 19th century in Germany for his cynical humor and biting mockery being communicated in an artful way. His humorous drawings and caricatures are remarkable for the extreme simplicity and expressiveness of his pen-andink line. I have only limited knowledge of englisch speaking authors, but from my point of view, I would consider the works of Wilhelm Busch very much alike the style of writing of Mark Twain.[5] It was his careful observation of the contemporary society and of the general human weaknesses, which he put into drawings and texts of ironical humor.

Ah, how oft we read or hear of

Boys we almost stand in fear of!

For example, take these stories

Of two youths, named Max and Moritz,

Who, instead of early turning

Their young minds to useful learning,

Often leered with horrid features

At their lessons and their teachers.

(First lines of ‘Max and Moritz’ in english translation)

Two Fun-Loving Rascals

Max and Moritz are by no means obviously naughty children, but fun-loving rascals instead. The tone of voice in the first lines of the story is already greatly exaggerated. And that’s just what Wilhelm Busch wanted to achieve – irony. Busch’s classic tale of the terrible duo Max and Moritz has since become a proud part of the culture in German-speaking countries. Even today, parents usually read these tales to their not-yet-literate children. To this day in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, a certain familiarity with the story and its rhymes is still presumed, as it is often referenced in the media. The two leering faces are synonymous with mischief, and appear almost logo-like in advertising and even graffiti.

Sawing through the bridge planks (third trick)

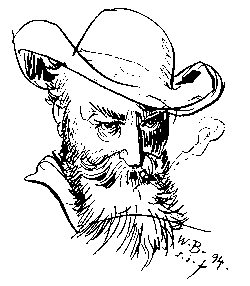

Wilhelm Busch

Wilhelm Busch was born in 1832 at Wiedensahl in Hanover. After studying at the academies of Dusseldorf, Antwerp and Munich, he joined in 1859 the staff of Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), the leading German comic paper, and was, together with Adolf Oberländer, the founder of modern German caricature. His humorous illustrated poems, such as Max and Moritz, Der heilige Antonius von Padua, Die Fromme Helene, Hans Huckebein and Die Erlebnisse Knopps des Junggesellen, play, in the German nursery, the same part that Edward Lear‘s nonsense verses do in England [6]. The types created by him have become household words in his country. He invented the series of comic sketches illustrating a story in scenes without words, which served as an inspiration for many other leading caricaturists.

Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908)

Busch was a serious and reserved man who lived for many years of his life in seclusion in the province. He himself attached little value to his picture stories and called them “Schosen” (French: chose = thing, thing, quelque chose = something, something). At the beginning he regarded them only as a breadwinner, with whom he could improve his oppressive economic situation after an aborted art study and years of financial dependence on his parents. His attempt to establish himself as a serious painter failed because of his own standards. Wilhelm Busch destroyed most of his paintings, the surviving ones often seem like improvisations or fleeting colour notes and are difficult to assign to a particular painterly direction. His poetry and prose poetry, influenced by Heinrich Heine‘s style and Arthur Schopenhauer‘s philosophy, were not understood by the public, who associated his name with comic picture stories. He sublimated with humour that his artistic hopes were disappointed and that he had to take back exaggerated expectations of himself. This is reflected both in his picture stories and in his literary work.

Rudolph Dierks, The Katzenjammer Kids panel from 1901.

Max and Moritz

In November 1863 Busch started to work on Max and Moritz and in winter 1865 he offered the manuscripts to his publisher Heinz Richter in Dresden. Richter objected the manuscript because of poor sales prospects. But, Busch’s former publisher Kaspar Braun in Munich purchased the right to the picture stories for 1,000 gulden, a huge sum, which corresponds roughly to two annual wages of a craftsman; the business was successful. And in the long run it should also prove successful for Braun. Although the sales of “Max and Moritz” were initially very sluggish, the sales figures improved from the second edition (1868) on. There were overall 56 editions until Wilhelm Busch’s death in 1908 and almost 500,000 sold copies. It was translated into English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish and Walloonian.

In 1997, more than 281 translations to dialects and languages were recorded. Critics have primarily ignored those, but since 1870 pedagogues found that they have an undesirable influence on the moral development of young people. Busch’s works definitely influenced comics, he has been described as the “first virtuoso” of picture stories. Since the second half of the 20th century, Wilhelm Busch was given the title “Forefather of Comics”. A true recreation of “Max and Moritz” is The Katzenjammer Kids by native German Rudolph Dirks, published in the New York Journal since 1897 every Saturday, about kids named Max and Fritz. They were created after publisher William Randolph Hearst‘s suggestion to fabricate a pair of siblings that followed the original pattern invented by Busch. The Katzenjammer Kids are regarded one of the oldest, continuous comic strips.

Faszination Comic 2007 – Wilhelm Busch und die Folgen, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] (German) Max und Moritz at project gutenberg

- [2] (English) Max and Maurice at project gutenberg

- [3] (German) Max und Moritz at wikisource

- [4] (German) Wilhelm Busch – Deutsches Museum für Karikatur und Zeichenkunst

- [5] Mark Twain – Keen Observer and Sharp-tongued Critic, SciHi Blog, November 30, 2012.

- [6] Edward Lear and his Book of Nonsense, SciHi Blog, May 12, 2015.

- [7] Wilhelm Busch at Wikidata

- [8] Faszination Comic 2007 – Wilhelm Busch und die Folgen, Splash Comics @ youtube

- [9] Timeline for Wilhelm Busch, via Wikidata