Louis Daguerre (1787-1851)

On August 19, 1839, French artist and physicist Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, after announcing his invention to the French Academy of Sciences, went public with his newly developed photographic process called Daguerrotype, the wold‘s first practicable photographic process.

The Invention of Photography

Actually, Louis Daguerre did not invent photography, but, in 1829, he partnered with Nicéphore Niépce,[4] an inventor who had produced the world’s first heliograph in 1822 and the first permanent camera photograph four years later. Niépce used a coating of bitumen of Judea to make the first permanent camera photograph. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to light and the unhardened portion was then removed with a solvent. A camera exposure lasting for hours or days was required. Niépce and Daguerre later refined this process, but unacceptably long exposures were still needed. But, let’s take a look at Daguerre’s biography first.

The Ruins of Holyrood Chapel, painting by Daguerre (1824).

A Panorama Painter

Louis Daguerre was born in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val-d’Oise, France on November 17, 1787, and grew up in a French middle-class family. His father, a royalist despite the outbreak of the French Revolution, named one of his daughters after Marie Antoinette. Because of political upheaval during and after the French Revolution, Daguerre’s formal education was limited and inconsistent. At age 13, he apprenticed in architecture and in 1804 Daguerre moved to Paris to study and practice scene painting for the opera. He became acquainted with panoramic painting working with Pierre Prévost, the first French panorama painter. Exceedingly adept at his skill of theatrical illusion, he became a celebrated designer for the theatre, and later came to invent the diorama, which opened in Paris in July 1822. The Diorama was a Paris illusionistic exhibition that contained paintings on large translucent screens, which seemed to come to life with skillful light manipulation. As an artist, Daguerre was interested in creating realistic renderings and utilized a camera obscura to aid his efforts. In hopes of simplifying the process, he became intrigued with the idea of permanently fixing an image chemically, as were many others during the period.

“…the daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” (Louis Daguerre)

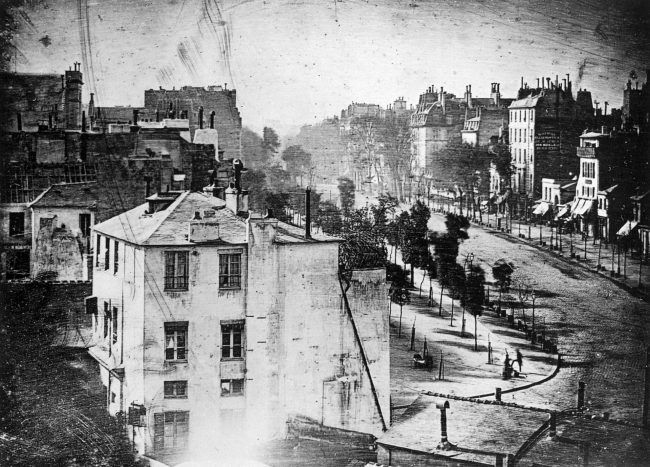

View of the Boulevard du Temple, taken by Daguerre in 1838 in Paris,

From Experiment to Commercial Success

Not until 1838 had Daguerre’s continued experiments progressed to the point where he felt comfortable showing examples of the new medium to selected artists and scientists in the hope of lining up investors. François Arago, a noted astronomer and member of the French legislature, moreover the perpetual secretary of the French academy of sciences, was among the new art’s most enthusiastic admirers. Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre’s studio. Arago succeeded to promote Daguerre in both the Académie des Sciences and the Chambre des Députés, securing the inventor a lifetime pension in exchange for the rights to his process. Only on August 19, 1839, was the revolutionary process explained, step by step, before a joint session of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts, with an eager crowd of spectators spilling over into the courtyard outside. The process revealed on that very day seemed magical to all who participated. Each daguerreotype is a remarkably detailed, one-of-a-kind photographic image on a highly polished, silver-plated sheet of copper, sensitized with iodine vapors, exposed in a large box camera, developed in mercury fumes, and stabilized (or fixed) with salt water or sodium thiosulphate. Although Daguerre was required to reveal, demonstrate, and publish detailed instructions for the process, he wisely retained the patent on the equipment necessary to practice the new art.

“I have seized the light. I have arrested its flight.” (Louis Daguerre)

On Arago’s recommendation, the rights to Daguerre’s trial were bought up by the French government and made public as a gift to the world. In return, Daguerre received a lifelong pension of 6,000 francs and the heir of Niépce, Isidor Niépce, a lifelong pension of 4,000 francs. In recognition of his achievements, Daguerre received numerous awards. As early as 1839, he was elected an honorary member of the National Academy of Design in New York. In 1842 he was admitted to the Prussian Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts as a foreign member.

Limitations of Daguerre’s Process

But, the daguerreotype process also had serious limitations compared to today’s chemical photographic process. The imprinted images that were obtained through Daguerre’s technique were clear, but fragile. They were also relatively heavy since they were produced on metal, further weighed down by the need for a cover plate or frame to protect their delicate surface layers. In addition, each daguerreotype image was unique and could not be copied, a problem that was avoided in the paper-based calotype process developed by Henry Fox Talbot at approximately the same time.

Daguerre’s Legacy

Louis Daguerre died on 10 July 1851 from “the bursting of a pulsed artery tumour” – presumably from an aneurysm – in Petit-Bry-sur-Marne near Paris. After his death, his photographic method was still used in Europe until about the mid-1850s, in the USA until the 1860s, as the daguerreotype portrait of Abraham Lincoln from 1864, which has adorned the newly designed American 5-dollar bill since 2006, shows. During this period, which was coming to an end, the daguerreotype was replaced by new and cheaper photographic methods.

The Daguerreotype – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 2 of 12, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Louis Daguerre, Photo Pioneer Honored By Google: Interesting Facts

- [2] Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography at the Metmuseum

- [3] Louis Daguerre at Molecular Expressions

- [4] Nicéphore Niépce and the World’s First Photograph, SciHi Blog

- [5] Daguerre and the daguerreotype An array of source texts from the Daguerreian Society web site

- [6] Works by or about Louis Daguerre at Internet Archive

- [7] Louis Daguerre at Wikidata

- [8] The Daguerreotype – Photographic Processes Series – Chapter 2 of 12, 2014, George Eastman Museum @ ypoutube

- [9] Daguerre, Louis (1839). History and Practice of the Photogenic Drawing on the True Principles of the Daguerreotype with the New Method of Dioramic Painting. London: Stewart and Murray.

A practical description of that process called the daguerreotype.

- [10] Timeline of Pioneers of Photography, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #14 | Whewell's Ghost