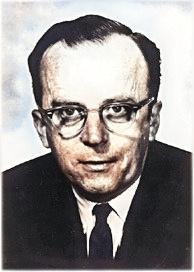

J.C.R. Licklider (1915-1990)

On March 11, 1915, American psychologist and computer scientist J.C.R. Licklider, known simply as J.C.R. or “Lick“, was born. He is particularly remembered for being one of the first to foresee modern-style interactive computing and was one of the most distinguished Internet pioneers.

“[…] we are entering a technological age in which we will be able to interact with the richness of living information – not merely in the passive way that we have been accustomed to using books and libraries, but as active participants in an ongoing process, bringing something to it through our interaction with it, and not simply receiving something from it by our connection to it.”

— J. C. R. Licklider, (1968) [7]

Early Years and Work in Psycho-Acoustic

Licklider was born in St. Louis, Missouri and his engineering talents became clear pretty early, when he built model airplanes as a child. He enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis, where he received a bachelor of arts degree in 1937. Licklider received his master degree one year later, majoring in physics, psychology, and mathematics. After receiving a PhD in psychoacoustics from the University of Rochester in 1942, Licklider moved to Harvard where he started working at the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory. There, he conducted field experiments in B-17 and B-24 bombers during the war years to investigate the effects of high altitudes on voice communication and static noise and other sources of interference on radio receivers. In the psychoacoustics field, Licklider is most remembered for his 1951 “Duplex Theory of Pitch Perception“, which formed the basis for modern models of pitch perception. He was also the first to report binaural unmasking of speech.

MIT and the SAGE Program

Licklider’s interest in information technologies evolved in the late 1940s. His early ideas foretold of graphical computing, point-and-click interfaces, digital libraries, e-commerce, online banking, and software that would exist on a network and migrate wherever it was needed. The scientist moved to MIT, where he was appointed associate professor and served a committee that established a psychology program for engineering students. Also, he worked on the SAGE-Program, a Semi-Automatic Ground Environment creating a computer-aided air defense system. Licklider worked there as a human factors experts, which convinced him of the great potential for computer interfaces.

Interactive Graphics

When a research group on the human factor was set up in 1953 in the psychology section of MIT’s economics department, Licklider took the lead and took a handful of his most intelligent colleagues and students from Lincoln Lab. The group was transferred to the social psychologists of work management at the Sloan School of Management in 1954, but dealt with completely different management problems. She worked in the then completely new field of experimental cognitive psychology and explored, for example, whether computers were suitable models for the various cognitive abilities of humans. After the first dissertation from this department, the management of MIT wanted to work on more scientifically conventional terrain. Since Licklider did not receive any permanent positions for his department, his sought-after colleagues gradually emigrated. Licklider then explored a new field of interest and by a rather accidental encounter at the Lincoln Lab with computer architect Wesley A. Clark he got to know the computer TX-2, which he had constructed in 1958. The TX-2 was one of the first computers to display interactive graphics on screen. Licklider was fascinated by the meetings he had with Clark, who from then on took up an ever-increasing part of his time and turned away more and more from psychology to computer science.

A SAGE operator’s terminal Image: Joi Ito

Time Sharing and Man-Machine Symbiosis

“It seems reasonable to envision, for a time 10 or 15 years hence, a ‘thinking center’ that will incorporate the functions of present-day libraries together with anticipated advances in information storage and retrieval. The picture readily enlarges itself into a network of such centers, connected to one another by wide-band communication lines and to individual users by leased-wire services. In such a system, the speed of the computers would be balanced, and the cost of the gigantic memories and the sophisticated programs would be divided by the number of users.”

– J. C. R, Licklider, Man-Computer Symbiosis, (1960)

Licklider left MIT to join the acoustics and information technology company Bolt Beranek and Newman (BBN) in 1957, where he became Vice Presient and bought the first production PDP-1 computer and conducted the first public demonstration of time-sharing. Thereafter, numerous computer scientists followed Licklider to join BBN. Based on research at BBN, Licklider summed up his visions in 1960 in the groundbreaking article Man-Computer-Symbiosis, with which he established his reputation as a computer scientist in a broad scientific public because they were counted among the boldest and most imaginative visions of those days. Particularly since they came from a psychologist who hadn’t had specialist knowledge of computers four years earlier, they received additional attention. In the article, Licklider described the concept of a simpler interaction between man and computer, and his ideas were summarized in a central thesis:”A close connection between man and” the electronic members of the partnership “would eventually lead to cooperative decision-making processes.” In addition, human decisions would be made with the help of computers, but without “inflexible dependency on pre-defined programs“. Computers should, of course, be available for tasks that they can do best, which Licklider believes are routine tasks, while people can use the energy and time they gain to make better insights and decisions.

Licklider’s Internet Vision

During his active years in computer science, Licklider managed to conceive, manage, and research the fundamentals that led to modern computers and the Internet as we know it today. His 1960 scientific paper on the Man-Computer Symbiosis was revolutionary and foreshadowed interactive computing. This inspired many other scientists to continue early efforts on time-sharing and application development. One of the scientists funded by Licklider’s efforts was the famous American computer scientist Douglas Engelbart, whose efforts led to the invention of the computer mouse.[4]

In August 1962, in a series of memos, Licklider described a global computer network that contained almost all the ideas that now characterize the Internet. With a huge budget at his disposal, he hired the best computer scientists from Stanford University, MIT, UCLA, Berkeley and selected companies for his ARPA research. He jokingly described this approximately a dozen or so researchers, with whom he had a close exchange, as the “Intergalactic Computer Network“. About six months after starting his work, he distributed an opinion in this unofficial panel, criticizing the problems of the proliferating multiplication of different programming languages, debugging programs and documentation procedures and initiating a discussion on standardization, as he saw this as a threat to a hypothetical, future computer network.

Work at DARPA

In 1962, the director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, later DARPA), the Defense Ministry’s research department, offered Licklider to take over the Command and Control Research department and set up a behavioural research department, for which he was provided a Q-32 by SDC. Licklider was also assured full autonomy for his research. He then moved to ARPA in October 1962 and could now pursue his ideas on time-sharing and human-machine interaction and propagate them in government circles. The computer establishment criticized Licklider’s program at the time with the argument that time-sharing was an inefficient use of computer resources and should therefore not be pursued further. About six months after the beginning of his activity, he distributed a statement to this unofficial committee in which he criticized the proliferation of different programming languages, debug programs and documentation procedures and initiated a discussion about standardization, as he saw a danger for a future computer network here. He emphasized the necessity of “creating conditions for an integrated network operation“, as was also the case with the human “intergalactic computer network” with regard to language, writing and communication channels.

The Birth of the ARPANET

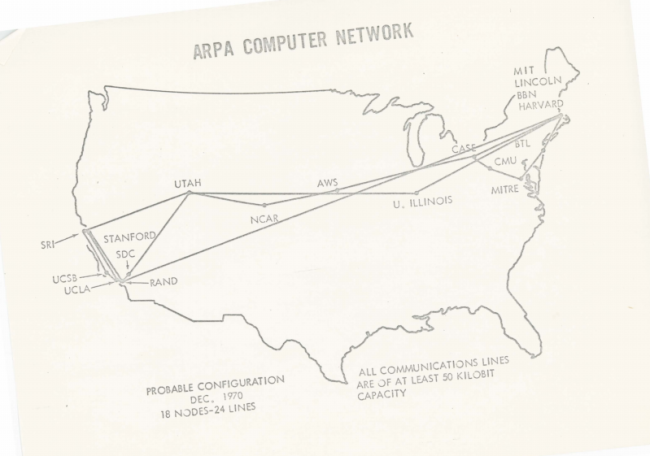

The map of ARPANET in December 1970, it contains 18 Nodes and 24 Lines.

When Licklider left ARPA in 1964, his department was called “Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO)” and no longer focused on command and control systems in war scenarios, but on time-sharing systems, computer graphics and the improvement of programming languages. His successor wasIvan Sutherland,[6] the world’s leading expert in computer graphics. He in turn brought Bob Taylor from NASA to ARPA in 1965. Like Licklider – whom he had known since 1962 – Taylor was an expert in psychoacoustics and was significantly influenced by him. From 1966 Taylor took over the management of the department. The new director of ARPA, Charles M. Herzfeld, had also attended lectures by Licklider on computers and dialogue. In 1968/69, based on Licklider’s research, the ARPANET, the forerunner of the Internet, was created.

Later Years

In 1968 Licklider became part of the MAC project at MIT, where a large mainframe computer was designed to be shared by up to 30 simultaneous users, each sitting at a so called typewriter terminal. The first computer time-sharing system and one of the first online setups with the development of Multics were established. In 1973, Licklider returned to DARPA as Head of IPTO and oversaw the spin-off of the Arpanet from DARPA, before moving again to MIT in 1975, where he ended his career. Another merit of Licklider is largely unknown: In the past, Licklider was unable to obtain a doctorate in computer science at any American university, but his work led to the establishment of the corresponding research base at four of the country’s best universities. In 1994, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the ARPANET, which had already been out of service for four years, the Clinton government honoured the numerous participants. 19 pioneers of the Arpanet/Internet were present and two special awards were presented. For Licklider, who died in 1990, his very elderly wife Louise received the special award. The other went to Bob Kahn,[8] the leading developer of the TCP/IP protocol.

Computer Networks – The Heralds Of Resource Sharing (Arpanet, 1972), [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Man-Computer Symbiosis

- [2] J. C. R. Licklider And The Universal Network

- [3] Before the Altair – The History of Personal Computing

- [4] Doug Engelbart and the Computer Mouse, SciHi Blog, November 17, 2012.

- [5] The Birth of the Internet, SciHi Blog, October 29, 2013.

- [6] Ivan Sutherland – Well, I Didn’t Know it was Hard, SciHi Blog

- [7] J.C.R. Licklider, Robert Taylor: “The Computer as a Communication Device”. Science and Technology 76, pp. 21-31 April 1968.

- [8] Robert Kahn and the Internet Protocol, SciHi Blog

- [9] Oral history interview with J. C. R. Licklider at Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

- [10] Glenn Fowler (3 July 1990). “Joseph C.R. Licklider Dies at 75 – Foresaw New Uses for Computers”. New York Times

- [11] J. C. R. Licklider at Wikidata

- [12] Computer Networks – The Heralds Of Resource Sharing (Arpanet, 1972), via Internet Archive, Brandon Goodrich @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of Internet Pioneers, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: JCR Licklider – Ideas for the Digital Age | Delightful & Distinctive COLRS