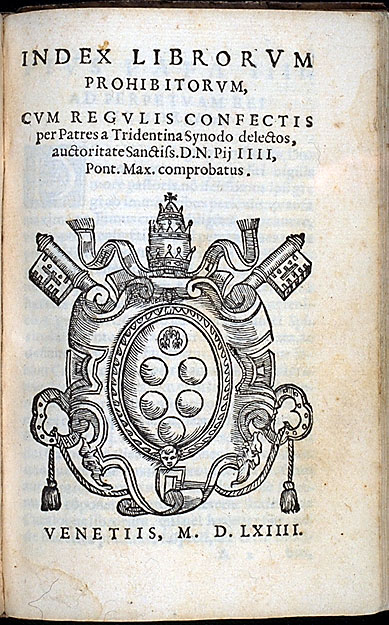

Title page of Index Librorum Prohibitorum

(Venice 1564)

On June 14, 1966, the Roman Catholic Church abolished their famous list of banned books, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum or shorter simply, the Index, that had been installed almost 500 years ago. Actually, it was soon clear after the invention of the printing press that the written word could also be dangerous, especially if it can be published in large quantities. Once Johannes Gutenberg had presented the printing press including the printing process back in 1440 whereby new ideas were enabled to spread rapidly and in masses, the authorities soon were afraid that ‘dangerous thoughts’ might spread too far and gain too much popularity.[2]

The First Censorship Agency

The very first to introduce official censorship in book printing was Berthold von Henneberg (1441-1504), archbishop and electorial prince of Mainz, in Germany. He became well know for his edict, issued in March 22, 1485, in which he introduced censorship for all books being translated from Greek or Latin into any other language. By that he tried to prevent the spreading of ideas and discussions beyond the realms of scientists, philosophers, and scholars into the broad public. In addition, Berthold ordered the Frankfurt city council to examine together with ecclesiastic authorities all printed books exhibited at the Frankfurt spring bookfair and, if necessary, to prohibit their selling. In order to put this in practice the electorate of Mainz together with the Imperial city of Frankfurt installed the first censorship agency of the world in 1486.

Desacration by Translation

As the Church and also secular authorities had realized that the printing press was able to foster the spreading of unwanted thoughts and arguments, censorship soon became commonplace. For the same reason authorities prevented the translation of the Holy Bible from Latin into the people`s languages, because — according to Henneberg – ‘the order of the holy mass’ could be ‘desacrated’ by translating it into German.

The Exclusive Supremacy of the Clergy

Pope Leo X (1475-1521) emphasized this interdiction because he was afraid of a rampant dissemination of ‘aberrant faith’. If everybody would be able to read the Holy Bible, it will be desacrated and the exclusive supremacy of the clergy to interpret the holy scriptures will be in danger. However, the practice of banning books for theological reasons has a much older history. As a result of the 1st Council of Nicaea, Roman Emperor Constantine I burned the writings of Arius in 325 and made their possessions punishable by death.[3] The first purely ecclesiastical ban on books dates back to the year 400. Under the presidency of Theophilus of Alexandria, it was decreed that no one in Egypt should “read or possess” the writings of Origen. In 446, Pope Leo the Great had the Manichean writings burned. The first synod to order the burning of the texts condemned by her was the 3rd Council of Constantinople in 681.

Medieval Censorship

In the context of theological disputes as well as in the fight against heretics and other believers, the popes banned writings again and again in the Middle Ages. These prohibitions were enforced by the church in cooperation with the secular rulers. It was not the Pope and the Curia, but the universities that were primarily responsible for the continuous review and, if necessary, the prohibition of books. In addition, there were again and again independent censorship procedures and prohibitions of books by secular rulers or individual bishops. Peter Abaelard was sentenced by the Council of Soissons in 1121 to burn his book on the Holy Trinity. Twenty years later, after the Council of Sens in 1141, Pope Innocent II condemned him to burn his writings. Pope Gregory IX and other popes repeatedly ordered the burning of the Jewish Talmud.

Preventive Censorship

Preventive censorship, i.e. a careful examination of the writing by the censorship authority even before it was allowed to be printed, had been installed via a Papal bull by Pope Innozenz VIII (1432–1492), while repressive censorship, i.e. the interdiction of dissemination of already printed books via decree or even confiscation, had been installed by Papal bull, too. The later by Pope Alexander VI. (1430–1503). For the purpose of censorship, every book that the Catholic church allowed to be printed carried a so-called ‘Imprimatur‘ (latin for ‘let it be printed’) issued by the ecclesiastic authorities. Any contravention was inflicted with draconic punishments, such as extremely high fines, disbarment, or even excommunication.

Title copper for the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. The Holy Spirit ignites the fire that serves to burn a book, copperplate engraving from 1711.

The Implementation of the Index

At the instigation of Cardinal Carafa, the later Pope Paul IV, in 1542 Paul III appointed six Cardinals with the bull Licet ab initio as General Inquisitors for the whole Church and thus created the Roman Inquisition, more precisely the Congregatio Romanae et universalis inquisitionis, the predecessor of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The reason for this centralization was the fact that there had always been different views at different universities as to which books should be forbidden and which should be allowed. Nor could the Congregation rule out the spread of Reformation ideas at the universities. And last but not least the number of books had increased considerably due to the invention of mechanical printing by Johannes Gutenberg. The task of the Inquisition was primarily to fight Protestantism and heretics in general. Since books and printed works had been recognized as effective tools of the Reformation, the Inquisition established a structured church censorship system. The most important means of this censorship was the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, first published in 1559, which was continually updated.

How to Put a Book on the Index

The indexing process began with the display of a book, which could come either from the curia itself or from outside. Often the location of the first print was sufficient for an initial suspicion. In the preliminary proceedings, the secretary of the Congregation with two experts first examined whether censorship proceedings against the book should be initiated at all. The main procedure consisted of one, in the case of Catholic authors two written expert opinions, which were evaluated by an expert committee, the consultants, and discussed in a meeting. At the end of the meeting there was a proposal for a resolution, which was presented to the cardinal body of the Inquisition. The Cardinals, in turn, decided whether the book was dangerous or not, and the Pope made the final decision to include it in the index.

Who’s on the Index?

The last official edition of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum was published in 1948 with supplements until 1962. The index last contained over 6000 titles which could not be reconciled with the doctrine of faith or morals of the church. The Index existed for almost 500 years until Pope Paul VI repealed it finally in 1966. What books were on this famous list? If you take a look, you will find romantic novels of Honoré de Balzac,[4] the famous Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert,[5,6] but also the works of astronomer Galileo Galilei, Heinrich Heine, philosopher Immanuel Kant [8] or even existentialist Jean Paul Sartre [7] – all of them very well known to you, because we have already reported about them here at SciHi Blog.

The Abolition of the Index

One of the major reasons for the abolition of the Index was besides others, that the Roman Catholic Church was not able to cope with the permanently growing masses of books being published in the course of the 20th century. Therefore, a careful but also prompt examination was not possible anymore. Besides, the continuation of the Index including its draconic punishments wasn’t up-to-date anymore. On the other hand, the Second Vatican Council, in its 1963 decree Inter mirifica, had expressed its opinion on modern means of communication and had pleaded for a constructive debate with the new media.

Vatican: Forbidden Works, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Eine kurze Geschichte der verbotenen Bücher – Index Librorum Prohibitorum, at Biblionomicon

- [2] Johannes Gutenberg – Man of the Millennium, SciHi Blog

- [3] Constantine and the Battle at the Milvian Bridge, SciHi Blog

- [4] Honoré de Balzac and the Comédie Humaine, SciHi Blog

- [5] Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, SciHi Blog

- [6] Jean Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert and the Great Encyclopedy, SciHi blog

- [7] A Writer should not Allow Himself to be Turned into an Institution – Jean-Paul Sartre, SciHi Blog

- [8] Immanuel Kant – Philosopher of the Enlightenment, SciHi Blog

- [9] Facsimile of the 1559 index

- [10] Vatican: Forbidden Works, Journeyman Pictures @ youtube

- [11] Hilgers, Joseph (1908). “Censorship of Books”. The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Robert Appleton Company.

- [12] Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books, Dec 22, 2005