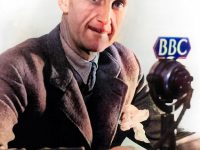

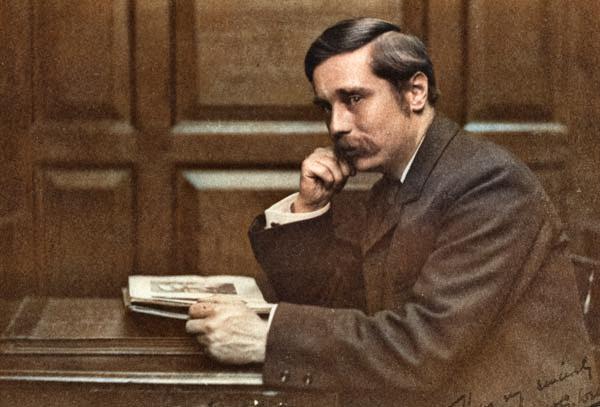

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946)

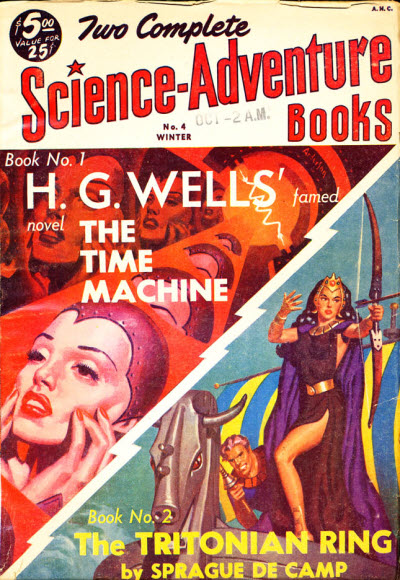

For sure you have seen the classic movie ‘The Time Machine‘, where the Victorian epoch time traveler went to a future far, far away into the world, where the old struggle of good against evil continued. Then, you also might have heard about the story, where aliens from Mars started war against Earth, but finally are going to die because of Earth’s microbes. Or maybe also the story, when famous actor and director Orson Welles in 1938 produced a radio show from this story, which was mistaken by a lot of American people to be a true radio report about an ongoing alien invasion of the USA, causing a real life panic?[5]

“We were making the future,” he said, “and hardly any of us troubled to think what future we were making. And here it is!”

— H. G. Wells, When The Sleeper Wakes (1899)

H. G. Wells – The Father of Science Fiction

Responsible for all this was British novelist Herbert George Wells, who wrote ‘The Time Machine‘ as well as ‘War of the Worlds‘. Born in Kent in 1866, H.G. Wells was also a prolific writer in many other genres besides science fiction, including contemporary novels, history, politics and social commentary, even writing text books and rules for war games. Together with Jules Verne [8] and Hugo Gernsback,[9] Wells has been referred to as “The Father of Science Fiction“.

Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress

Before he came to writing, he had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper, as a pupil-teacher, and started studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley in London. H.G. Wells’s first non-fiction bestseller was “Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought” published in 1901. It is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Predicting what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits as well as for its misses.

“The past is but the beginning of a beginning, and all that is or has been is but the twilight of the dawn.”

— H. G. Wells, The Discovery of the Future (1901)

Forseeing the Future

As an example, Wells predicted that trains and cars would result in the dispersion of population from cities to suburbs, moral restrictions would decline as men and women seek greater sexual freedom, German militarism would be defeated, and he also forsaw the existence of a European Union. On the other hand, he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that “my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea“.

Wells’s works were reprinted in American science fiction magazines as late as the 1950s

The Scientific Romances

Some of his early novels, called “scientific romances”, invented a number of themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), and The First Men in the Moon (1901). Also, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was “A Modern Utopia” (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with “no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all“. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living, as e.g., by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet, 1906), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933). He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939).

World War I

With the novel The World Set Free (1914), Wells anticipated the development of the atomic bomb and later became its eponym. He was inspired by the book The Nature of Radium (1909) by the English chemist Frederick Soddy, which summarized the state of knowledge on radioactivity at the time. Wells supported the First World War and called it the “war to end all wars”. In 1918, he briefly became head of propaganda against Germany under Lord Northcliffe at Crewe House, a department of the Ministry of Information. Here he designed a scheme for the post-war design of Europe. His most important work, written and published during the war, was Mr. Britling sees it Through (1916).

The Idea of a World State

Shortly after the war (1920) he visited Soviet Russia and took part in the Washington Conference in 1921. In the following years he travelled a lot and spent some winters outside the harsh English climate which was not conducive to him. Although he continued to write novels – his most important novel in the period between the First and Second World Wars was The World of William Clissold (1926) – he turned more and more to spreading his ideas. The four works The Outline of History (1920), The Open Conspiracy (1928), Science of Life (1929) and The Work Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1932) were all designed to popularize the idea of creating a world state. In his view, this was the only alternative to a relapse into barbarism and final destruction.

“Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the early twentieth century than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible. And as certainly they did not see it. They did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands.”

— H. G. Wells, The World Set Free (1914)

Meeting Orson Welles

On his last trip to the USA in 1940, he met the young Orson Welles, who on 30 October 1938 adapted his novel about the War of the Worlds to a radio play and thus caused some confusion in New York because of the feared landing of aliens, which is often passed down as “mass panic”.[5] For Wells, the Second World War was the confirmation that humanity had lost control of the forces it had unleashed and was unstoppably opposed to its own destruction – to which the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 contributed in particular.

After suffering from diabetes mellitus for a long time, H. G. Wells died in his London home on 13 August 1946. The exact cause of death was not disclosed.

Bruce Clarke, Anachronism in Science Fiction and Science: The Case of H.G. Wells [12]

References and further Reading:

- [1] H. G. Wells in Wikipedia

- [2] H. G. Wells’ bibliography in Wikipedia

- [3] video of an interview with H. G. Wells

- [4] Works by or about H. G. Wells at Internet Archive

- [5] Orson Welles and the 1938 Radio Show Panic, SciHi Blog

- [6] H. G. Wells papers at University of Illinois

- [7] Around the World in 80 Days, SciHi Blog

- [8] The Man who Invented Science Fiction – Hugo Gernsback, SciHi Blog

- [9] H. G. Wells at Wikidata

- [10] Works about or by H. G. Wells, at Wikisource

- [11] Bruce Clarke, Anachronism in Science Fiction and Science: The Case of H.G. Wells, Western Civilization, Texas Tech University @ youtube

- [12] Future Tense – The Story of H. G. Wells at BBC One – 150th anniversary documentary (2016)

- [13] “When H. G. Wells Split the Atom: A 1914 Preview of 1945”, by Freda Kirchwey, in The Nation, posted 4 September 2003

- [14] “Wells, Hitler and the World State”, by George Orwell. First published: Horizon. GB, London. Aug 1941.

- [15] Timeline for H. G. Wells, via Wikidata