Gustave Whitehead (1874 – 1924)

On January 1, 1874, German-born aviation pioneer Gustav Albin Weißkopf was born. He emigrated from Germany to the United States and called himself Gustave Whitehead. He designed and built gliders, flying machines, and engines between 1897 and 1915. Controversy surrounds published accounts and Whitehead’s own claims that he flew a powered machine successfully several times in 1901 and 1902, predating the first flights by the Wright Brothers in 1903.[1]

Gustav Weißkopf – Background and Education

Gustav Weißkopf was born in 1874 as the second of seven children of the married couple Karl Ernst Weißkopf (1848-1887) and Babette née Wittmann (1849-1886) in Leutershausen, Bavaria. His parents had married six months before his birth, and the couple’s first child was his sister Eva Babetta, born in 1871. His father came from Ansbach, his mother from Colmberg. In 1886, the mother Babette Weißkopf died at age of only 37 after the family had moved to Höchst am Main (today part of Frankfurt am Main). The father Karl Ernst Weißkopf died shortly after in 1887. The siblings were separated, and Gustav came to live with his grandparents in Ansbach along with his brother Karl. Gustav Weißkopf initially began an apprenticeship as a bookbinder in 1887, but broke it off and was apprenticed to a locksmith instead. He also broke off this apprenticeship in the first year, this time because he went away from Ansbach without permission in 1889. From June to August 1889, he worked as a day laborer in Höchst am Main.

Becoming Gustave Whitehead

Little is known about his further life until he became traceable again eight years later in the USA. He presumably emigrated to Porto Alegre in Brazil. After trying his hand for a short time in the then completely undeveloped interior, he came to Rio de Janeiro. Probably around the year 1895 he immigrated to the USA in an unknown way. Gustav Weißkopf never renounced his German citizenship or applied for or accepted another citizenship. In the USA he wrote his name adapted to the English language “Gustave Whitehead“. According to his own statements, he worked for a time as a crew member on sailing ships before immigrating to the USA. In Brazil, he built and flew gliders, according to his statements. He said he observed the flight of condors in Chile and albatrosses at Cape Horn. He had caught one of these birds in order to study their wingspan and their relation to weight. According to his statements, he returned to Germany once again to meet Otto Lilienthal and to become his collaborator and student.[2]

The Boston Aeronautical Society

Weißkopf’s life can be documented again for the first time in 1897. In the two previous years, the Boston Aeronautical Society had endeavored to bring Lilienthal, who was world-famous at the time, to Boston, where he was to give lectures and practical flying lessons. After Lilienthal’s death in August 1896, the Boston Aeronautical Society decided instead to have a Lilienthal glider rebuilt. Gustav Weißkopf was hired for this task probably because of his alleged experience in building and flying gliders in Brazil and his alleged collaboration with Otto Lilienthal. Gustav Weißkopf built two gliders in the service of the Aeronautical Society, both of which were unfit for flight. As a result, he was dismissed and left Boston. He went to New York, where he found work in a factory making sporting goods and toys. After his marriage in 1897, Weisskopf moved with his family via Baltimore and Johnstown in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, to Pittsburgh in 1899, where he found work in a coal mine.

First Flight

Here he befriended fellow worker Louis Darvarich, who helped him build airplanes. Darvarich stated in an affidavit dated July 19, 1934, that he had flown with Whitehead: “It was either in April or May 1899 that I was present and flew with Mr. Whitehead (Weisskopf), who succeeded in getting his steam engine powered machine off the ground. The flight, at a height of about 8 meters, extended for about a mile. It took place in Pittsburgh with Mr. Whitehead’s monoplane. We failed to fly around a three-story building, and when the plane crashed, I was badly burned by the steam, because I had heated the boiler. Because of that, I had to spend several weeks in the hospital. I remember the flight clearly. Mr. Whitehead was unhurt, for he had been sitting in the front part of the machine and had steered it from there.” A New York newspaper carried an interview with Whitehead in 1901 in which he mentioned this flight.[3]

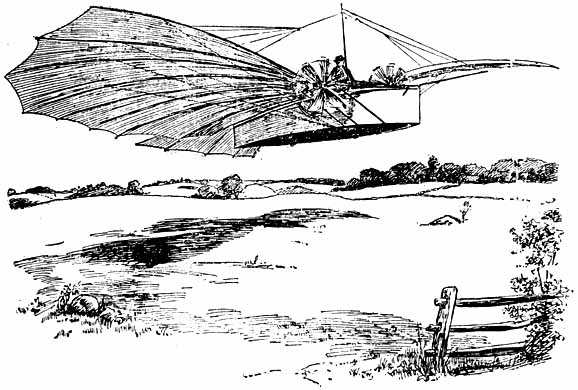

The drawing which accompanied the article on page 5 of 18 August 1901 Bridgeport Herald

The Flying Machine

In 1900, Gustav Weißkopf had settled in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and worked as a night watchman for the Willmot&Hobbs company, which gave him enough time during the day to pursue his interest in designing and building flying machines with engines of his own design. He was able to meet the aviation enthusiast Stanley Y. Beach and his father, the editor of Scientific American, Frederick C. Beach, to financially support his efforts. He recruited helpers from the neighborhood. In the Minneapolis Journal of July 26, 1901, Weisskopf reported a first flight in an unmanned machine he had built on May 3, 1901, unfolding its wings of bamboo cane and cotton, starting its two propeller-driven second engine, and two subsequent flights with 220 pounds of ballast instead of crew, ultimately more than 12 feet high and a half-mile wide.[4] The wing and tailplane of design No. 21 were similar in shape to those used by Lilienthal. In addition, No. 21 had a kind of boat hull, fitted with a home-made 10-horsepower engine for the landing gear and a 20-horsepower engine for the two propellers. The tail fin pivoted up and down as an elevator. The aircraft had no rudder or ailerons. For rotation about the yaw axis, it was possibly intended to operate the two propellers at different speeds.

The No. 21 aircraft. Whitehead sits beside it with daughter Rose in his lap; others in the photo are not identified. A pressure-type engine rests on the ground in front of the group.

Manned Motor Powered Flight

On August 18, 1901, the Sunday Bridgeport Herald reported on an unmanned flight with 220 pounds of ballast and a subsequent first manned powered flight by Weißkopf with a soft landing after half a mile on the previous Wednesday, August 14, 1901.[5] Riding on the road with wings folded on its 30 cm high wooden disc wheels, the machine is certified to have reached a speed of about 45 km/h. As eyewitnesses present on the spot at Fairfield, the author, who is not named, mentions, besides himself and the pilot Weißkopf, his two assistants James Dickie and Andrew Celli.

Founding a Factory

In the fall of 1901, Weisskopf received $10,000 in capital from New York entrepreneur Herman Linde and established an airplane factory where he planned to manufacture light and powerful aircraft engines in particular. The St. Louis Republic quoted Weisskopf on November 18, 1901, as saying that his backer and he could have an airplane on the market in a few months. However, in January 1902, the partnership broke up. Linde took over the aircraft factory and in 1904 made it known that he would build a self-launching aircraft. In the spring of 1902, Gustav Weißkopf announced that on January 26, he had made two successful flights of almost two miles and seven miles in a new airplane that he had christened No. 22. No photo of No. 22 is known. Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the aircraft. In the ten years following these alleged flights of two and seven miles respectively, Gustav Weißkopf never again succeeded in reproducing this supposed performance, although he still built numerous aircraft and made many unsuccessful takeoff attempts.

The End of Whitehead’s Entrepreneurship

In 1910, Stanley Beach ended Weißkopf’s many years of financial support. Looking back, he later gave as the reason that Weißkopf had never succeeded in building a self-launching aircraft by 1910. In 1911, Weisskopf received $5,000 from a contractor to design and build an engine for testing an early version of a helicopter. After the engine failed to perform as promised, his client sued Weisskopf for repayment. Since Weißkopf was insolvent, he was seized in 1912, which meant the end of his independence.

Then End

After losing his company, Weisskopf worked as a factory worker in Bridgeport until his death. Weisskopf died of a heart attack at his home on October 10, 1927. That Weißkopf’s 1901 powered flight has remained controversial to this day is due to the paucity of sources, the lack of a photograph of the flying machine, and numerous inconsistencies in existing sources. Weisskopf’s many years of involvement with flying machines and the construction of working aircraft engines are evident. Even intensive research since 1937, however, has not been able to definitively determine the boundary between truth and fiction to this day.

Tom Crouch, The Strange Case of Gustave Whitehead, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Wright Brothers Invented the Aviation Age, SciHi Blog

- [2] Otto Lilienthal, the Glider King, SciHi Blog

- [3] Ship that will fly like a bird may soon be placed on the market. In: New York Telegram, 19. November 1901, p. 10; Scan in: gustave-whitehead.com.

- [4] Library of Congress: A Flying Machine that flies a little. In: The Minneapolis Journal. 26. Juli 1901

- [5] Flying. In: Bridgeport Herald. Volume 9, Nr. 567, 18. August 1901, S. 5 , via Google News

- [6] Gustave Whitehead’s Flying Machines

- [7] Gustave Whitehead – What Did He Do?

- [8] Delear, Frank (March 1996), “Gustave Whitehead and the First-Flight Controversy”, Aviation History, Weider History Group, pp. 1–10

- [9] Brinchman, Susan O’Dwyer (2015). Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight. Apex Educational Media.

- [10] The German Aviation Pioneer Museum Gustav Weißkopf

- [11] Gustave Whitehead at Wikidata

- [12] Tom Crouch, The Strange Case of Gustave Whitehead, at the Engineers’ Club in Dayton, Ohio , 24. June 2013, via youtube

- [13] Timeline of Aviation Pioneers born before 1880, via Wikidata and DBpedia

For more reliable, documented info on Gustave Whitehead, see http://www.gustavewhitehead.info and the book “Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight” (Brinchman, 2015). The article above does not mention that Smithsonian has had a contract with the Wright heirs since 1948, following Orville’s death, requiring the institution to recognize Orville and the Wright Flyer as first in powered flight. If anyone else is recognized they lose the Wright Flyer, their premiere exhibit, which will then return to the heirs. Thus, history has been written by contract, in order to obtain and retain an exhibit. This contract is shown on the site above and in the book referenced. I am the author and last surviving early Whitehead researcher.