Frederick the Great of Prussia examines the potato harvest (1886)

On 24, March, 1756, Prussian king Frederick the Great passed the circular order that should ensure the cultivation and deployment of potatoes in his country. Actually, citizens received this only rather refusing, because this subterranean vegetable seemed rather suspicious to them. But there is the saying that the king used a clever trick to convince his subjects…

“I appreciate the potato only as a protection against famine, except for that, I know of nothing more eminently tasteless.”

– Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) , in ‘The Physiology of Taste’ (1825)

A Short History of Potatoes

Originally, wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to southern Chile with its origins in the area of present-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia, where they were domesticated 7,000–10,000 years ago. It has since spread around the world and become a staple crop in many countries. Following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, the Spanish introduced the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century. In 1552 Spanish historian and secretary of Hernan Cortez, Francisco López de Gómara, referenced the potato first in his chronicle ‘Historia general de las Indias‘. Although he himself never visited the Americas, he remarked that the inhabitants of the Colloa Altiplano near the Lake Titicaca of the Peruanian Andes were living on on corn and papas, i.e. potatoes, and that they would become hundred years and older. Slowly adopted by distrustful European farmers, but soon enough it became an important food staple and field crop that played a major role in the European 19th century population boom.

Conquering Europe

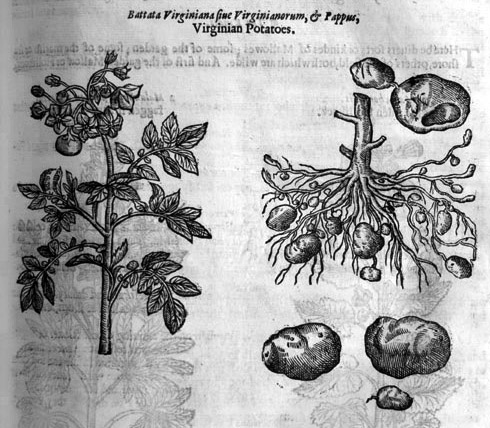

On its way from South America to Spain, the potato made a stopover on the (Spanish) Canary Islands. This is known because in November 1567 three barrels containing potatoes, oranges and green lemons were shipped from Gran Canaria to Antwerp, and in 1574 two barrels of potatoes were shipped from Tenerife via Gran Canaria to Rouen. If one assumes that it took at least five years to obtain so many potatoes that they could become an export article, the naturalization of the plant took place on the Canary Islands at the latest in 1562. Because of its beautiful flowers and lush foliage, potatoes were often imported into Europe as pure ornamental plants and included as rare plants in botanical gardens.

John Gerard (1545-1612): The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes. London, 1633.

What the peasant doesn’t know, he will not eat

In Prussia it should take until the mid 18th century until the potato was finally adopted as nutrition. There it was Frederick the Great who was responsible for its first extensive deployment. He saw the potato’s potential to help feed his nation and lower the price of bread, but faced the challenge of overcoming the people’s prejudice against the plant. He coined also the popular phrase ‘Potatoes instead of Truffles!‘ and besides his famous military campaigns he also launched a propaganda campaign for the subterranean field crop. And for both campaigns his army was playing a major part to become a success. But the royal order alone did not succeed with his stubborn subjects who refused to eat the subterranean bulbs. In Prussia as in the rest of Germany there was the saying: ‘Was der Bauer nicht kennt, frisst er nicht. [What the peasant doesn’t know, he will not eat]‘. Actually, the town of Kolberg officially replied to the king’s order: “The things [potatoes] have neither smell nor taste, not even the dogs will eat them, so what use are they to us?“

His Cunning Plan…

Therefore, he came up with a cunning plan. There is the saying that he had cultivated first potato fields around the area of Berlin and ordered his army to rigorously guard the fields against any thefts. At least this was he was making his subjects to believe. In fact, Frederick ordered his army not to take care too much and to look away or to pretend sleeping. Therefore, the king’s subjects became suspicious that the field fruits must be rather precious to be guarded so strictly. And in the end, the subjects tried to steel the potatoes whenever the soldiers pretended to be distracted or unobservant. And this exactly the king originally had in mind.

You Will Always Find Some Potatoes on his Grave

I was living in the neighborhood of Sanssouci palace in Potsdam, where also King Frederick the Great has his last resting place at the terrace of the vineyard at Sanssouci. There, he has a small gravestone with his name written on it. And besides some flowers, you will always find a few potatoes laying there as a reminiscence regarding his role during the introduction of the subterranean field fruit in Germany.

Gravestone of Frederick the Great with flowers and potatoes in Sanssouci

Walter De Jong, The Complete Book of Potatoes, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Niemann, Christoph (14 October 2012). “The Legend of the Potato King“. The New York Times.

- [2] Jeff Chapman: The History of the Potato, The History Magazine

- [3] Frederick the Great at Wikidata

- [4] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [5] Jean Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert and the Great Encyclopedy, SciHi Blog

- [6] Walter De Jong, The Complete Book of Potatoes, Albert R. Mann Library @ youtube

- [7] The World Potato Atlas, released by the International Potato Center in 2006

- [8] Atlas of Wild Potatoes (2002), Systematic and Ecogeographic Studies on Crop Genepools 10, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute

- [9] Timeline for Frederick the Great, via Wikidata

Pingback: TB 200101 The Temptation of Forbidden Tubers | The Thunderbolt

Pingback: Reattanza Psicologica, cosa può imparare il Marketing dalla quarantena – Miriam Battistella

Pingback: Potatoes: Global Food Staple – Sarah Bowman Answers

Pingback: 'Vua khoai tây' và chiến lược xây dựng thương hiệu thành công đầu tiên trên thế giới

Pingback: Design to resolve a notion, not an issue | by - CoBlog

Pingback: Join clubhouse - Farketing