Francois Villon (1431-1489)

On January 5, 1463, the Death sentence to Francois Villon, best known French poet of the late Middle Ages, was remitted by a pardon from King Charles VII into 10 years of banishment. Villon is best known as a ne’er-do-well who was involved in criminal behavior and got into numerous scrapes with authorities. Nevertheless, Villon wrote about some of these experiences in his poems and became famous.

Through wind, hail or frost my living’s made.

I am a lecher, and she’s a lecher with me.

Which one of us is better? We’re both alike:

The one as worthy as the other. Bad rat, bad cat.

We both love filth, and filth pursues us;

We flee from honor, honor flees from us,

In this brothel where we ply our trade.

– Francois Villon, Ballade de la Grosse Margot (Le Grand Testament)

Early Years

Villon was born in Paris in 1431 under the name François de Montcorbier or François des Loges, the same year that Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in Rouen. Some sources give the date as April 19, 1432 (April 1 according to the old Julian calendar).[9] In his works, he only refers to himself as Villon. All that we know about his life stems from his own poems complemented by court or other civil documents. According to his telling, Villon was born in poverty and raised by a foster father. The surname “Villon” was the name he adopted from his foster father, Guillaume de Villon, chaplain in the collegiate church of Saint-Benoît-le-Bétourné, and a professor of canon law, who took Villon into his house.

First Blood and Banishment

Villon became a student in arts, perhaps at about twelve years of age. He received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Paris in 1449 and a master’s degree in 1452. Little is known about his life for the next few years, but on June 5, 1455, the first major recorded incident of his life occurred. In the company of a priest and a girl, he met a Breton, Jean le Hardi, a master of arts, who was also with a priest, Philippe Sermoise. A scuffle broke out, daggers were drawn and Sermaise, who is accused of having threatened and attacked Villon and drawn the first blood, not only received a dagger-thrust in return, but a blow from a stone, which struck him down deadly. Villon fled, and was sentenced to banishment – a sentence which was remitted in January 1456 by a pardon from King Charles VII after he received the second of two petitions which made the claim that Sermoise had forgiven Villon before he died.

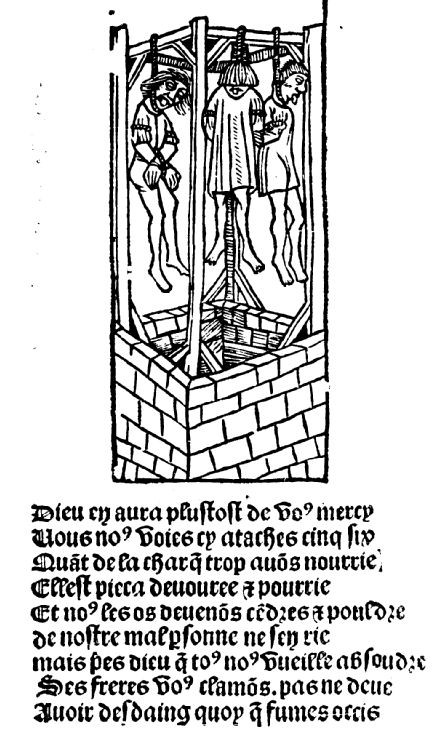

La Ballade des pendus, édition Treperel, Paris, 1500.

Back in Paris

Villon returned to his home in Paris, and wrote Le Lais (The Legacy), also known as Le Petit Testament, one of Villon’s most important works. Villon claimed to have finished the poem at Christmas, while at the same time he met up with a number of acquaintances and later stole 500 gold crowns from a coffer at the College of Navarre, where the community kept their funds. In Le Lais, Villon shows himself composing the poem during the same hours he was orchestrating the robbery.[1] After leaving Paris, he probably went for a while to Angers. He certainly went to Blois and stayed on the estates of Charles, duc d’Orléans, who was himself a poet. Here, further excesses brought him another prison sentence, this time remitted because of a general amnesty declared at the birth of Charles’s daughter, Marie d’Orléans, on December 19, 1457. At some later time, Villon is known to have been in Bourges and in the Bourbonnais, where he possibly stayed at Moulins. But throughout the summer of 1461 he was once more in prison. He was not released until October 2, when the prisons were emptied because King Louis XI was passing through.[3]

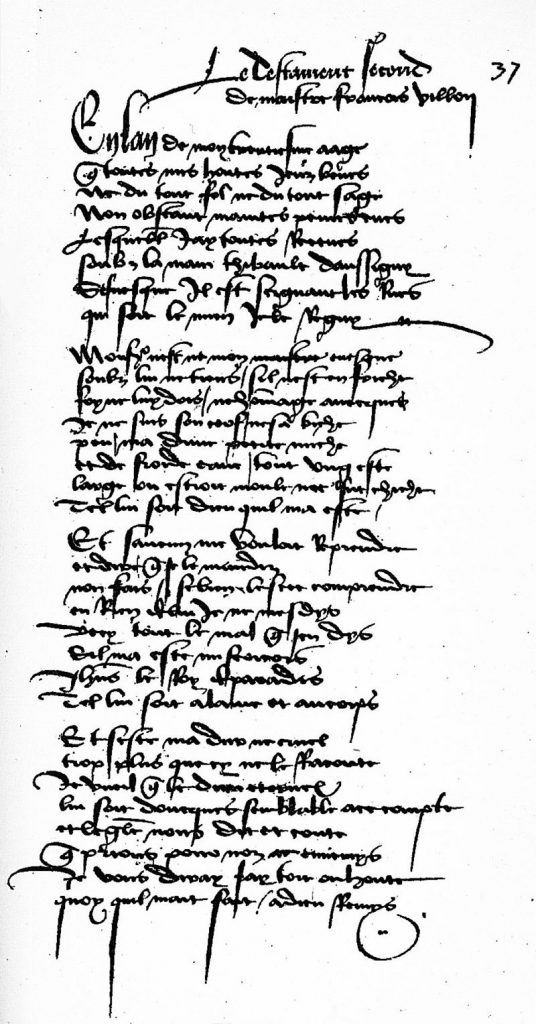

A page from Villon’s Le grand testament. Kungliga biblioteket in Stockholm, Sweden.

Le Testament

Now, Villon composed what is considered his masterpiece, Le Testament. The over two thousand verses are propelled by the immediate possibility of a death sentence for Villon by hanging and balance the extremes of anger and religious fervor. Villon’s luck finally seemed to have run out when he was once again arrested for falling into a street quarrel and sentenced to death at the gallows. While awaiting his death sentence, Villon composed “Ballad of Hanged Men” and “I Am Francois, They Have Caught Me.” A last minute appeal to Parliament reduced his sentence to ten years banishment from Paris on January 5, 1463. At the time, Villon was only 34 years old. He left the city and was never heard from again.[1]

Francois Villon’s Legacy

Francois Villon is today perhaps the best-known French poet of the Middle Ages. His works surfaced in several manuscripts shortly after his disappearance in 1463, and the first printed collection of his poetry came out as early as 1489. More than one hundred printed editions followed, and Villon’s poetry has been translated into more than twenty-five languages. Over the next five hundred years authors as the classical French critic Nicolas Boileau, the English poet A. C. Swinburne, and the American poet Ezra Pound praised Villon.[6] Villon’s life has been romanticized in novels, plays, and motion pictures, and many modern literary anthologies cite him as the best of the late medieval poets in France.[2] Villon’s poems are sprinkled with mysteries and hidden jokes: they are peppered with the slang of the time and the underworld subculture in which Villon moved. Also Bertolt Brecht was strongly influenced by Villon [4], desinging the main character of his drama “Baal” (1918) after him. Also some of the lyrics Brecht wrote for “Threepenny Opera” are translations or paraphrases of poems by Villon.

David Evans, Debussy, Banville and the Problem with Fixed-Form Poems, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Francois Villon at poets.org

- [2] Francois Villon at poetryfoundation.org

- [3] Francois Villon at Encyclopedia Britannica

- [4] The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht, SciHi Blog, February 10, 2014.

- [5] Francois Villon at Wikidata

- [6] The Cantos of Ezra Pound will last as long as there is any Literature, SciHiu Blog

- [7] Works by or about François Villon at Internet Archive

- [8] François Villon Ballad about the Plump Margot. French-English parallel text.

- [9] Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans, SciHi Blog

- [9] François Villon, sur Wikisource (in French)

- [10] David Evans, Debussy, Banville and the Problem with Fixed-Form Poems, Gresham College @ youtuibe

- [11] Timeline of Francois Villon, via Wikidata