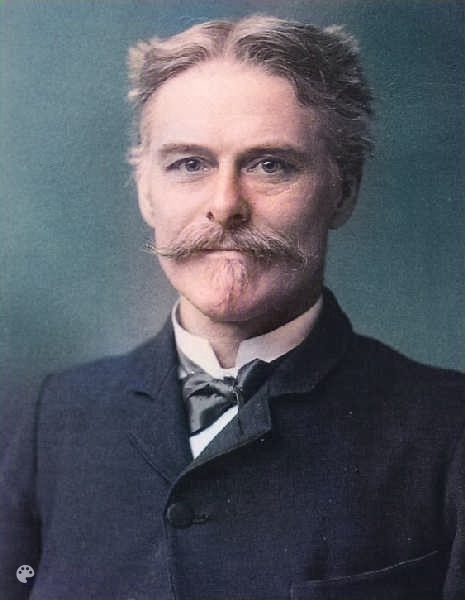

Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897)

On July 28, 1840, American paleontologist and comparative anatomist Edward Drinker Cope was born. Being s well as a noted herpetologist and ichthyologist, he was a founder of the Neo-Lamarckism school of thought. This school believed that changes in developmental (embryonic) timing, not natural selection, was the driving force of evolution. Cope thought that groups of species that shared similar developmental patterns could be grouped into more inclusive groups (i.e. genera, families, and so on). His contributions helped to define the field of American paleontology.

Edward Drinker Cope – Early Years

Edward Drinker Cope was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the eldest son of Alfred and Hanna Cope, orthodox members of the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers operating a lucrative shipping business. At age three, Edwards mother died, but his stepmother, Rebecca Biddle, soon filled the maternal role. The Copes began teaching their children to read and write at a very young age, and took Edward on trips across New England and to museums, zoos, and gardens. Cope’s interest in animals became apparent at a young age, as did his natural artistic ability. At age nine, Edward was sent to a day school in Philadelphia and in 1853 he visited the Friends’ Boarding School at Westtown, near West Chester, Pennsylvania, where Edward studied algebra, chemistry, scripture, physiology, grammar, astronomy, and Latin.

An Interest in Biology

Biology began to interest Edward soon and he studied natural history texts in his spare time. After the summer break in 1854 and 1855, his father did not return Edward to school. Instead, he attempted to turn his son into a gentleman farmer, which he considered a wholesome profession that would yield enough profit to lead a comfortable life. While working on farms, Edward continued his education on his own. In 1858, he began working part-time at the Academy of Natural Sciences, reclassifying and cataloguing specimens, and published his first series of research results in January 1859. Instead of working the farm his father bought for him, Edward rented out the land and used the income to further his scientific endeavors.

Academic Career

Finally, his father gave up and Edward attended the University of Pennsylvania in the 1861 and/or 1862 academic years, studying comparative anatomy. In 1861, he published his first paper on Salamandridae classification; over the next five years he published primarily on reptiles and amphibians. In 1863–1864 during the American Civil War, Edward traveled through Europe, taking the opportunity to visit the most esteemed museums and societies of the time. Upon returning to Philadelphia in 1864, the Cope family made every effort to secure Edward a teaching post as the Professor of Zoology at Haverford College, a small Quaker school where the family had philanthropic ties. Cope’s return to the United States also marked an expansion of his scientific studies; in 1864, he described several fishes, a whale, and the amphibian Amphibamus grandiceps, his first paleontological contribution.

The Marls Pits of Haddonfield

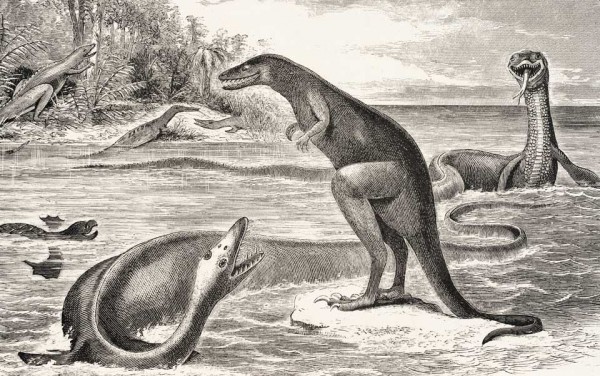

He resigned from his position at Haverford and moved his family to Haddonfield, in part to be closer to the fossil beds of western New Jersey. Pleading with his father for money to pursue his career, he finally sold the farm in 1869. The fossils he found in the Marl pits in Haddonfield became the focus of several papers, including a description in 1868 of Elasmosaurus platyurus and Laelaps. The 1870s were the golden years of Cope’s career, marked by his most prominent discoveries and rapid flow of publications. Among his descriptions were the therapsid Lystrosaurus (1870), the archosauromorph Champsosaurus (1876), and the sauropod Amphicoelias (1878), possibly the largest dinosaur ever discovered. During the peak years, Cope published around 25 reports and preliminary observations each year. The hurried publications led to errors in interpretation and naming—many of his scientific names were later canceled or withdrawn.

The Bone Wars

After inheriting his father’s estate in 1875, Cope now had the finances to hire multiple teams to search for fossils for him year-round and he advised the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition on their fossil displays. Cope’s most famous competitor was Othniel Charles Marsh of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale,[1] who should become his archrival. From 1877 to 1892, a time also referred to as the “Bone Wars“, both paleontologists used their wealth and influence to finance their own expeditions and to procure services and dinosaur bones from fossil hunters. Their search for fossils led them west to rich bone beds in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Each of the two paleontologists used underhanded methods to try to out-compete the other in the field, resorting to bribery, theft, and destruction of bones. Each scientist also attacked the other in scientific publications, seeking to ruin his credibility and have his funding cut off. By the end of the Bone Wars, both men had exhausted their funds in the pursuit of paleontological supremacy.

Dryptosaurus (formerly Lealaps) confronting Elasmosaurus. Hadrosaurus foraging in background. Note that the head of Elasmosaurus was erroneously placed by Cope on the “short end” now known to be the tail. From: Cope, E.D. “The fossil reptiles of New Jersey,” in: American Naturalist, vol. 3 (1869), pp. 84-91.

Financial and Social Ruin

Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their attempts to disgrace each other, but their contributions to science and the field of paleontology were massive, and provided substantial material for further work. The efforts of the two men led to over 142 new species of dinosaurs being discovered and described, though today only 32 are valid. The products of the Bone Wars resulted in an increase in knowledge of prehistoric life, and sparked the public’s interest in dinosaurs, leading to continued fossil excavation in North America in the decades to follow.

The Batrachians of North America

In 1892, Cope (then 52 years old) was granted expense money for field work from the Texas Geological Survey. With his finances improved, he was able to publish a massive work on the Batrachians of North America, which was the most detailed analysis and organization of the continent’s frogs and amphibians ever mastered, and the 1,115-page The Crocodilians Lizards and Snakes of North America. In the 1890s, his publication rate increased to an average of 43 articles a year. Cope sold his collections to the American Museum of Natural History in 1895. In 1896, Cope began suffering from a gastrointestinal illness he said was cystitis. Edward Drinker Cope died on April 12, 1897, aged 57.

Denying Darwinian Evolution

Although he accepted evolution, Cope didn’t really accept Darwinian evolution. Cope’s original view on evolution, described in the paper “On the Origin of Genera” (1868), held that while Darwin’s natural selection may affect the preservation of superficial characteristics in organisms, natural selection alone could not explain the formation of genera. In Cope’s view, during embryological development, an organism could complete its growth with a new stage of development beyond its parents, taking it to a higher level of organization. Later individuals would inherit this new level of development—thus evolution was a continuous advance of organization, sometimes slowly and other times suddenly; this view is known as the law of acceleration. Cope’s beliefs later evolved to one with an increased emphasis on continual and utilitarian evolution with less involvement of a Creator. He became one of the founders of the Neo-Lamarckism school of thought, which holds that an individual can pass on traits acquired in its lifetime to offspring.[2] Cope’s theory of kinetogenesis, stating that the natural movements of animals aided in the alteration and development of moving parts, led him to openly support Lamarck’s theory of evolution.[6,2] Although the view has been shown incorrect, it was the prevalent theory among paleontologists in Cope’s time.

Final Years

In fewer than 40 years as a scientist, Cope published over 1,400 scientific papers, a record that stands to this day. He discovered a total of 56 new dinosaur species during the Bone Wars compared to Marsh’s 80. Although Cope is today known as a herpetologist and paleontologist, his contributions extended to ichthyology, in which he catalogued 300 species of fishes over three decades. In total, he discovered and described over 1,000 species of fossil vertebrates and published 600 separate titles. In 1896, Cope began suffering from a gastrointestinal illness he said was cystitis. Word of Cope’s illness spread, and he was visited by friends and colleagues; even in a feverish condition Cope delivered lectures from his bed. Cope died on April 12, 1897, 16 weeks short of his 57th birthday.

Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Othniel Charles Marsh and the Great Bone Wars, SciHi blog, October 29, 2014.

- [2] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the Evolution, SciHi blog, August 1, 2015.

- [3] Obituary: Edward Drinker Cope, in The American Naturalist, Vol. 31, No. 365 (May, 1897), pp. 412-413, The University of Chicago Press for The American Society of Naturalists.

- [4] Works of or about Edward Drinker Cope, at WikiSource

- [5] Biographical Memoir of Edward Drinker Cope, at National Academy of Sciences.

- [6] Edward Drinker Cope, American Paleontologist, at Britannica online

- [7] Edward Drinker Cope at Wikidata

- [8] Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, TED @ youtube

- [9] Timeline for Edward Drinker Cope via WIkidata