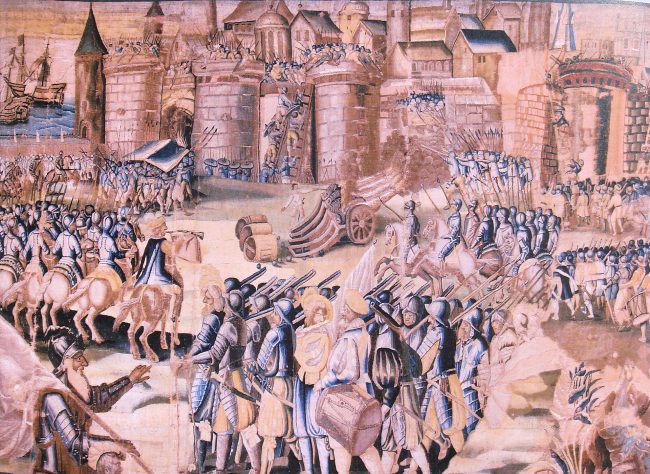

Painting by François Dubois, a Huguenot painter born circa 1529 in Amiens, who settled in Switzerland. Although Dubois did not witness the massacre, he depicts Admiral Coligny’s body hanging out of a window at the rear to the right. To the left rear, Catherine de’ Medici is shown emerging from the Louvre castle to inspect a heap of bodies

On April 13, 1519, Italian noblewoman and Queen of France Catherine de’ Medici was born. Catherine played a key role in the reign of her sons, and is blamed for the excessive persecutions of the Hugenots in particular for the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, in which thousands of Huguenots were killed in Paris and throughout France.

Catherine de Medici and Henry, Duke of Orleans

Catherine de’ Medici was born into a very influential family. Her father was made Duke of Urbino by his uncle Pope Leo X and her mother was from one of the most prominent and ancient French noble families. Unfortunately, her parents passed away early, wherefore she grew up with further family members. However, the family’s power decreased in 1527 and Pope Clement had to crown Charles Holy Roman Emperor. Charles’ troops laid siege to Florence and Catherine was supposed to be killed or exposed naked and chained to the city walls. The city surrendered in 1530 and Clement had Catherine move to Rome. When Francis I of France offered that his second son, Henry, Duke of Orléans, would marry Catherine, Clement highly supported the wedding. It took place in 1533, but the 14-year old’s saw only little of each other during their first year of marriage. Also it is assumed, that Prince Henry showed only little interest in his wife at all and for a long time they failed to produce any children. Unfortunately, Henry’s mistress gave birth to a daughter, which proved that he was fertile. He openly acknowledged her and added much pressure on Catherine. After quite a while, divorce was even discussed and Catherine now tried anything to get pregnant and in 1544, she finally gave birth to a son. The couples marriage did not improve after having several children, but Catherine was still respected as Henry’s consort. After the death of King Francis I, she became the queen consort of France and was crowned in the basilica of Saint-Denis.

Govenour of France

However, Catherine’s political power was very limited and Henry gave the Château of Chenonceau, which Catherine had wanted for herself, to Diane de Poitiers, who took her place at the center of power, dispensing patronage and accepting favours. After a sport accident, King Henry first lost his sight and speech and passed away on 10 July, 1559. Francis II became king at the age of fifteen and Catherine was not strictly entitled to a role in Francis’s government, because he was deemed old enough to rule for himself. Still, it is assumed that she played a major role in his decision making. When her son died in 1560, Catherine de Medici was appointed govenour of France and the nine year old Charles IX became King, who cried during his coronation.

The Massacre of Vassy

On 1 March 1562, in an incident known as the Massacre of Vassy, the Duke of Guise and his men attacked worshipping Huguenots in a barn at Vassy, killing 74 and wounding 104. Guise, who called the massacre “a regrettable accident”, was cheered as a hero in the streets of Paris while the Huguenots called for revenge. The massacre lit the fuse that sparked the French Wars of Religion. For the next thirty years, France found itself in a state of either civil war or armed truce. Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé raised a large army, formed an alliance with England and started seizing town after town in France. After further conflicts with her allies as well as her enemies, Catherine now rallied Hugenot and Catholic forces to retake Le Havre from England.

Catherine de’ Medici, engraving by Emanvels van Meteren, 1614

The Edict of Amboise

When Charles IX was declared of age, he still showed only little interest in government and Catherine decided to enforce the Edict of Amboise and revive loyalty to the crown. Philip II sent the Duke of Alba to tell Catherine to scrap the Edict of Amboise and to find punitive solutions to the problem of heresy. In 1566, Charles IX of France and Catherine de Medicis unsuccessfully proposed to the Ottoman Court a plan to resettle French Huguenots and French and German Lutherans in Ottoman-controlled Moldavia. In 1570, Charles IX married the daughter of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. Catherine de Medici was also eager for a match between one of her two youngest sons and Elizabeth I of England.[4] After Elisabeth died in childbirth in 1568, Catherine had touted her youngest daughter Margaret as a bride for Philip II of Spain. Now she sought a marriage between Margaret and Henry III of Navarre, with the aim of uniting Valois and Bourbon interests. Margaret, however, was secretly involved with Henry of Guise, the son of the late Duke of Guise and she faced great problems when Catherine found out about it.

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre

When Admiral Coligny was shot and wounded through his window, Catherine, who was said to have received the news without emotion, made a tearful visit to Coligny and promised to punish his attacker. Many historians have blamed Catherine for the attack. Two days later, the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre took place. It stained Catherine’s reputation ever since, since there is no reason to believe she was not party to the decision when on 23 August Charles IX ordered, “Then kill them all! Kill them all!“. Catherine and her advisers expected a Huguenot uprising to avenge the attack on Coligny. They chose therefore to strike first and wipe out the Huguenot leaders while they were still in Paris after the wedding of Henry and Catherine’s daughter Margaret. The massacre lasted for almost one week and spread across France where it persisted into the fall.

The Siege of La Rochelle (1572–1573) began soon after the St. Bartholomew massacre.

Aftermath

After Bartholomew’s Night, the king, and especially Catherine de Medici, held on to the old policy: the edict of Saint-Germain was to remain in force, meetings of the Huguenots were forbidden only to prevent armament, the crown did not under any circumstances want to bow to the Habsburgs seated in Spain, and an alliance with Philip II was still rejected. Pope Gregory XIII had a Te Deum sung and a commemorative coin minted as soon as the massacre became known. The painter Giorgio Vasari was commissioned to create three murals in the Sala Regia to commemorate the event. On Bartholomew’s night and the following days about 3000 people were murdered in Paris (several thousand in the province), in the great majority Huguenots. From August to October, similar massacres took place in other cities, including Toulouse, Bordeaux, Lyon, Bourges, Rouen and Orléans, killing between 5,000 and 15,000 people.

The Edict of Nantes

For the Protestants, the night of Bartholomew was a heavy defeat, and they lost a large part of their political leaders. It became clear in the following years that a majority of Paris and France could not be won over to the Reformation, since the majority of the population remained of the Roman Catholic faith and the political forces of the Protestant party were not sufficient to enforce the new Reformed faith by force. On the other hand, the Catholic Party was not strong enough to completely defeat the Protestants. The religious struggles in France therefore continued after the events of Bartholomew’s Night until the Huguenots were guaranteed legal certainty by King Henry IV of France in the Edict of Nantes in 1598.

Blood Wedding: The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in History and Memory by Barbara Diefendorf, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France

- [2] Portraits of Catherine de’ Medici

- [3] Catherine de Medici at BBC

- [4] The Virgin Queen – Elizabeth I., SciHi Blog

- [5] Catherine de Medici at Wikidata

- [6] . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [7] Blood Wedding: The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in History and Memory by Barbara Diefendorf, Boston University @ youtube

- [8] Goyau, Pierre-Louis-Théophile-Georges (1912). “Saint Bartholomew’s Day“. In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [9] St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Diarmaid McCulloch, Mark Greengrass & Penny Roberts (In Our Time, Nov. 27, 2003)

- [10] Timeline of French Religious Wars, via DBpedia and Wikidata