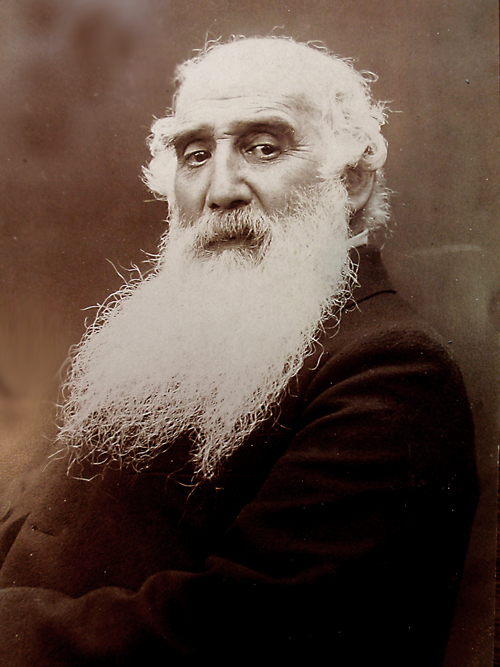

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

On July 10, 1830, Danish–French Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro was born. His importance resides in his contributions to both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He acted as a father figure not only to the Impressionists but to all four of the major Post-Impressionists, including Georges Seurat, Paul Cézanne,[6] Vincent van Gogh [5] and Paul Gauguin.[4]

“I am settled in France, and as for the rest of my history as a painter, it is bound up with the impressionistic group.”

– Camille Pissarro, circa 1856; as quoted in [11]

Camille Pissarro – Early Years

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born on the island of St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies (since 1917 the US Virgin Islands) to Frederick and Rachel Pissarro, a merchant of Portuguese Jewish descent. At age twelve Camille’s father sent him to boarding school in France. He studied at the Savary Academy in Passy near Paris. While a young student, he developed an early appreciation of the French art masters. However, when he returned to St. Thomas at age 17, his father preferred that he worked in his business and gave him a job working as a cargo clerk. He took every opportunity during those next five years at the job to practice drawing during breaks and after work. Pissarro was attracted to political anarchy, an attraction that may have originated during his years in St. Thomas. In 1852, he traveled to Venezuela with the Danish artist Fritz Melbye, who inspired Pissarro to take on painting as a full-time profession, becoming his teacher and friend. In 1855, Pissarro left for Paris, where he began working as assistant to Anton Melbye, Fritz Melbye’s brother, and studied at various academic institutions under a succession of masters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, and Charles-Francois Daubigny.

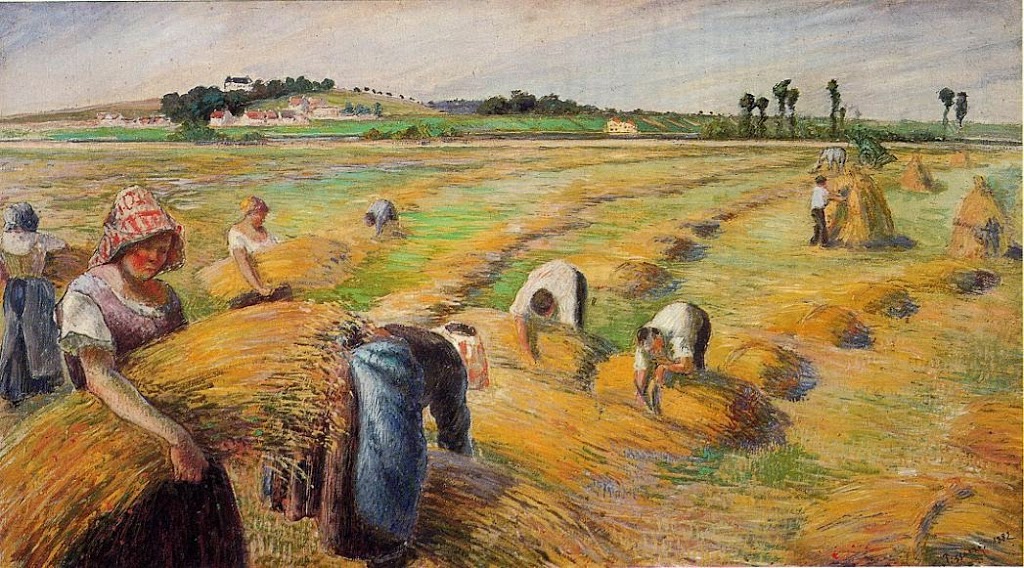

Camille Pissarro, The Harvest, 1882, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo

First Success

In 1859 Pissarro’s first painting was accepted and exhibited. His other paintings during that period were influenced by his tutor Camille Corot. He and Corot both shared a love of rural scenes painted from nature. It was by Corot that Pissarro was inspired to paint outdoors, also called “plein air” painting. Camille left his home in Louveciennes to move to England during the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune (1870-71) and, with Claude Monet,[7] he painted a series of landscapes around Norwood and Crystal Palace as well as studying English landscape painters in the museums. On returning home to Louveciennes at the end of the war a year later, Camille discovered that only 40 of his 1500 paintings – almost twenty years’ work – remained undamaged. In the summer of 1871 Camille settled in Pontoise where he was to remain for the next ten years, gathering a close circle of friends around him. Paul Cézanne repeatedly came to stay with him and under Camille’s influence learned to study nature more patiently.

The First Impressionist Exhibition

In the early 1870s Pissarro devoted a great deal of thought to the idea of creating an alternative to the Salon, a plan he discussed with Monet, Renoir, and others. They devised the idea of a society with a charter based on that of a local bakers’ union, and by January 1874 Pissarro helped found a cooperative along these lines. In April of that year the group held their first exhibition at the studio of the photographer Félix Nadar in Paris,[8] at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, a show that became known as the first Impressionist exhibition, which shocked and “horrified” the critics, who primarily appreciated only scenes portraying religious, historical, or mythological settings. In 1871, Pissarro married Julie Vellay, a maid in his mother’s household. Of their eight children, one died at birth and one daughter died aged nine. The surviving children all painted, and Lucien, the oldest son, became a follower of William Morris.[9]

Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning, 1897,

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Exploring new Themes and Methods

By the 1880s, Pissarro began to explore new themes and methods of painting to break out of what he felt was an artistic “mire”. As a result, Pissarro went back to his earlier themes by painting the life of country people. This period also marked the end of the Impressionist period due to Pissarro’s leaving the movement. It was Pissarro’s intention during this period to help “educate the public” by painting people at work or at home in realistic settings, without idealising their lives. In 1885 he met Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, both of whom relied on a more “scientific” theory of painting by using very small patches of pure colors to create the illusion of blended colors and shading when viewed from a distance. Adapting this Neo-impressionistic or Pointilistic style, Pissarro’s sales dipped as well as his rate of production. The family suffered considerably. Pissarro eventually turned away from Neo-Impressionism, claiming its system was too artificial. But, once he threw off the shackles of this labor-intensive direction, his natural verve reignited and his production soared. So did his prices and by the end of 1890s, the family enjoyed a comfortable income.

Later Years

In his older age Pissarro suffered from a recurring eye infection that prevented him from working outdoors except in warm weather. As a result of this disability, he began painting outdoor scenes while sitting by the window of hotel rooms. He often chose hotel rooms on upper levels to get a broader view. Pissarro died in Paris on 13 November 1903 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

T. J. Clark, “Pissarro and the Perfect Work of Art”, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Camille Pissarro’s biography on Camille Pissarro website

- [2] CamillePissarro.org

- [3] Camille Pissarro – French Impressionist and Painter

- [4] Paul Gauguin’s Way Back to Primitivism, SciHi Blog

- [5] There is no blue without yellow and without orange – Vincent van Gogh, SciHi Blog

- [6] Paul Cézanne – Breaking all the Rules, SciHi Blog

- [7] Claude Monet and the Invention of Impressionism, SciHi Blog

- [8] Nadar and How Photography became an Art, SciHi Blog

- [9] William Morris – Decorative Artist and Socialist Activist, SciHi Blog

- [10] 54 paintings by or after Camille Pissarro at the Art UK site

- [11] Henry G Stephens, Camille Pissarro’ Impressionist, in Brush and Pencil, Vol. XIII, no. 6 , March, 1904, p. 412-13

- [12] Camille Pissarro at Wikidata

- [13] T. J. Clark, “Pissarro and the Perfect Work of Art”, Kunstmuseum Basel @ youtube

- [14] Rewald, John, ed., with the assistance of Lucien Pissarro: Camille Pissarro, Lettres à son fils Lucien, Editions Albin Michel, Paris 1950;

- [15] Timeline for Camille Pissarro, via Wikidata

I agree that In the early 1870s, Pissarro wanted to create an alternative to the Salon, a plan he discussed with other dissatisfied artists. They must have loved the rather risky idea of a society with a charter because the cooperative was indeed created.

I wish I had seen their first exhibition at Félix Nadar Paris studio. No wonder the critics were shocked; they were traditionalists and the younger artists were more radical.

Helen