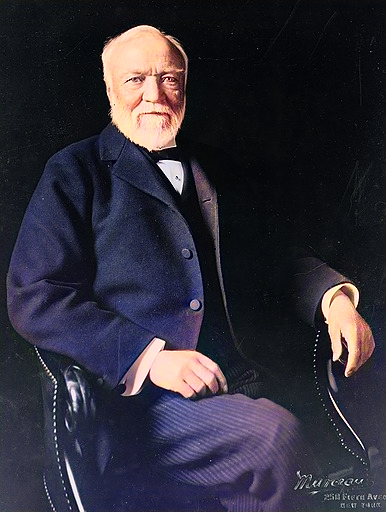

Andrew Carnegie (1835 – 1919)

On November 25, 1835, Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie was born. He led the enormous expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and was also one of the highest profile philanthropists of his era.

“Surplus wealth is a sacred trust which its possessor is bound to administer in his lifetime for the good of the community.”

— Andrew Carnegie, he Best Fields for Philanthropy, 1889

Early Life and Emigration

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, the son of weaver William Carnegie and Margaret Morrison, the daughter of shoemaker and tanner Thomas Morrison. He did not start school until the age of eight. His parents had let him decide for himself when he wanted to start school. Carnegie’s father’s employment situation deteriorated as the incipient machanization made manual weaving increasingly unprofitable. Expecting a better life, Andrew Carnegie’s family decided to leave Scotland and move to the United States in 1848. Carnegie started working at the age of 13 in Pittsburgh and was able to enjoy the local theater’s plays for free, which brought him closer to culture and especially Shakespeare. He worked hard and enjoyed studying at the local library once a week when it was opened for working boys.

Telegraphy and American Civil War

He got promoted several times and became a telegraph operator at the Pennsylvania Railroad Company in 1853. There the head of the Western Division of Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas A. Scott, became aware of Carnegie’s abilities and made him his secretary. Carnegie was promoted to the position of Pittsburgh Rail Division Manager. When Scott became Deputy Secretary of War in the American Civil War, Carnegie went with him to Washington, D.C. and worked as his right hand. Part of Carnegie’s mission was to organize the military telegraph system. Under his supervision, the transportation system enjoyed efficient service and highly contributed in the winning of the Union.

Becoming a Steel Tycoon

The 30 year old Carnegie made some smart investments in these years and devoted all energies to the ironworks trade, mostly in Pittsburgh. In the following years, Carnegie got also busy in the steel industry, which really paid off as well. During regular visits to Great Britain he noticed the rapid development in the iron industry. Henry Bessemer‘s converter from pig iron to steel impressed him, and he realized that steel would replace cast iron in the production of heavy goods.[5] In 1870 he built his first blast furnace, which used the ideas developed by Bessemer. In 1873 Carnegie built a steelworks named after the president of his former employer Pennsylvania Railroad, J. Edgar Thompson. This was a clever idea, because shortly after construction Carnegie received a large order from the same company.

Although he brought several partners into his company, Carnegie always insisted on holding the majority of his companies. He retained this majority when he merged his company with Henry Clay Frick’s in 1881. Carnegie had previously been one of the best customers of Frick, the coke producer, and the merger resulted in a rewarding vertical integration of the two companies. In 1889 Carnegie withdrew from the operational business and left the management to his business partner Henry Clay Frick. At that time, the company consisted of several steel mills and blast furnaces in the Pittsburgh area. In 1892, Frick merged all parts of the business into the Carnegie Steel Company. At the time, the company was the largest steel company in the world.

Andrew Carnegie’s Philanthropy

In his 1889 essay The Gospel of Wealth, Carnegie wrote: “The man who dies rich dies in shame.” True to this motto, Carnegie founded numerous foundations in the USA and Europe, some of which were or still are active in various fields. In an article for The North American Review in 1889, he described where he thought philanthropy was worthwhile. Carnegie wanted to help the hard-working and ambitious help themselves.

He built public libraries to use for free and laboratories in Pittsburgh. In the meantime, Carnegie enjoyed poetry and was befriended with Mark Twain.[4] Carnegie himself wrote rather radical books, like ‘Triumphant Democracy‘, published in 1886. This work caused some controversy in Britain, since it criticized the monarchical system and praised the American industry’s achievements. Impressed by the courageous actions of two men who, in 1904, saved the lives of many buried victims in a mine accident, but died together with 179 other men, he founded Carnegie Hero Trust Funds in eleven countries, which were intended to distinguish people who acted particularly selflessly. The foundations also provide financial aid to injured rescuers or the surviving dependants of deceased rescuers.

It was Carnegie’s concern to give everyone access to a free public library so that everyone could have the opportunity to be educated. In the USA, Carnegie – or the Carnegie Corporation – supported the establishment of a total of 1,681 public libraries between 1889 and 1923. Carnegie thus made a major contribution to the growth of public libraries. In total, he donated over $56 million to build 2,509 libraries. The Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University, after the merger with the Mellon Institute) was founded in 1900 with a $10 million donation from Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie wanted to build a world-class technical school for the children of Pittsburgh steelworkers. With a starting capital of $125 million, the bulk of his remaining assets, Andrew Carnegie established the Carnegie Corporation of New York charitable foundation in 1911. It was Carnegie’s last foundation, and it was designed to manage the remaining assets for the advancement of Carnegie’s philanthropic causes.

The Foundation, which ran Carnegie until his death in 1919 as its president, remains active today and has provided $1.35 billion in grants since its inception.

Man of Steel: Andrew Carnegie | The Gilded Age, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

- [2] The Many-Sided Andrew Carnegie: A Citizen of the Republic

- [3] Carnegie Birthplace Museum website

- [4] Mark Twain – Keen Observer and Shard-Tongued Critic, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Steel of Sir Henry Bessemer, SciHi Blog

- [6] Andrew Carnegie at Wikidata

- [7] Works by Andrew Carnegie at Project Gutenberg

- [8] Man of Steel: Andrew Carnegie | The Gilded Age, American Experience | PBS @ youtube

- [9] Livesay, Harold C. (1999). Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business, 2nd ed.

- [10] Bostaph, Samuel (2015). Andrew Carnegie: An Economic Biography. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- [11] Goldin, Milton (1997). “Andrew Carnegie and the Robber Baron Myth.” In: Myth America: A Historical Anthology, Volume II. Gerster, Patrick, and Cords, Nicholas. (editors.) St. James, NY: Brandywine Press

- [12] Hendrick, Burton Jesse (1993). The life of Andrew Carnegie (2 vol.) vol 2 online; scholarly biography

- [13] Timeline for Andrew Carnegie, via Wikidata